- Home

- Daniel Defoe

Captain Singleton

Captain Singleton Read online

Captain Singleton

Captain Singleton

Daniel Defoe

This page copyright � 2002 Blackmask Online.

http://www.blackmask.com

THE LIFE, ADVENTURES, AND PYRACIES, Of the Famous Captain SINGLETON: Containing

an Account of his being set on Shore in the Island of Madagascar, his Settlement

there, with a Description of the Place and Inhabitants: Of his Passage from

thence, in a Paraguay, to the main Land of Africa, with an Account of the

Customs and Manners of the People: His great Deliverances from the barbarous

Natives and wild Beasts: Of his meeting with an Englishman, a Citizen of London,

among the Indians, the great Riches he acquired, and his Voyage Home to England:

As also Captain Singleton's Return to Sea, with an Account of his many

Adventures and Pyracies with the famous Captain Avery and others.

LONDON: Printed for J. Brotherton, at the Black Bull in Cornhill, J. Graves in

St. James's Street, A. Dodd, at the Peacock without Temple bar, and T. Warner,

at the Black Boy in Pater-Noster-Row. 1720.

As it is usual for great Persons whose Lives have been remarkable, and whose

Actions deserve Recording to Posterity, to insist much upon their Originals,

give full Accounts of their Families, and the Histories of their Ancestors: So,

that I may be methodical, I shall do the same, tho' I can look but a very little

Way into my Pedigree as you will see presently.

If I may believe the Woman, whom I was taught to call Mother, I was a little

Boy, of about two Years old, very well dress'd, had a Nursery Maid to tend me,

who took me out on a fine Summer's Evening into the Fields towards Islington, as

she pretended, to give the Child some Air, a little Girl being with her of

Twelve or Fourteen Years old, that lived in the Neighbourhood. The Maid, whether

by Appointment or otherwise, meets with a Fellow, her Sweet-heart, as I suppose;

he carries her into a Publick-House, to give her a Pot and a Cake; and while

they were toying in the House, the Girl plays about with me in her Hand in the

Garden, and at the Door, sometimes in Sight, sometimes out of Sight, thinking no

Harm.

At this Juncture comes by one of those Sort of People, who, it seems, made it

their Business to Spirit away little Children. This was a Hellish Trade in those

Days, and chiefly practised where they found little Children very well drest, or

for bigger Children, to sell them to the Plantations.

The Woman pretending to take me up in her Arms and kiss me, and play with me,

draws the Girl a good Way from the House, till at last she makes a fine Story to

the Girl, and bids her go back to the Maid, and tell her where she was with the

Child; that a Gentlewoman had taken a Fancy to the Child, and was kissing of it,

but she should not be frighted, or to that Purpose; for they were but just

there; and so while the Girl went, she carries me quite away.

From this time it seems I was disposed of to a Beggar-Woman that wanted a pretty

little Child to set out her Case, and after that to a Gypsey, under whose

Government I continued till I was about Six Years old; and this Woman, tho' I

was continually dragged about with her, from one Part of the Country to another,

yet never let me want for any thing, and I called her Mother; tho' she told me

at last, she was not my Mother, but that she bought me for Twelve Shillings of

another Woman, who told her how she came by me, and told her that my Name was

Bob Singleton, not Robert, but plain Bob; for it seems they never knew by what

Name I was Christen'd.

It is in vain to reflect here, what a terrible Fright the careless Hussy was in,

that lost me; what Treatment she received from my justly enraged Father and

Mother, and the Horror these must be in at the Thoughts of their Child being

thus carry'd away; for as I never knew any thing of the Matter, but just what I

have related, nor who my Father and Mother were; so it would make but a needless

Digression to talk of it here.

My good Gypsey Mother, for some of her worthy Actions no doubt, happened in

Process of Time to be hang'd; and as this fell out something too soon for me to

be perfected in the Strolling Trade, the Parish where I was left, which for my

Life I can't remember, took some Care of me to be sure; for the first thing I

can remember of my self afterwards, was, that I went to a Parish-School, and the

Minister of the Parish used to talk to me to be a good Boy; and that tho' I was

but a poor Boy, if I minded my Book, and served God, I might make a good Man.

I believe I was frequently removed from one Town to another, perhaps as the

Parishes disputed my supposed Mother's last Settlement. Whether I was so shifted

by Passes, or otherwise, I know not; but the Town where I last was kept,

whatever its Name was, must be not far off from the Sea Side; for a Master of a

Ship who took a Fancy to me, was the first that brought me to a Place not far

from Southampton, which I afterwards knew to be Busselton, and there I tended

the Carpenters, and such People as were employ'd in Building a Ship for him; and

when it was done, tho' I was not above Twelve Years old, he carried me to Sea

with him, on a Voyage to Newfoundland.

I lived well enough, and pleased my Master so well, that he called me his own

Boy; and I would have called him Father, but he would not allow it, for he had

Children of his own. I went three or four Voyages with him, and grew a great

sturdy Boy, when coming Home again from the Banks of Newfoundland, we were taken

by an Algerine Rover, or Man of War; which, if my Account stands right, was

about the Year 1695, for you may be sure I kept no Journal.

I was not much concerned at the Disaster, tho' I saw my Master, after having

been wounded by a Splinter in the Head during the Engagement, very barbarously

used by the Turks; I say, I was not much concerned, till upon some unlucky thing

I said, which, as I remember, was about abusing my Master, they took me and beat

me most unmercifully with a flat Stick on the Soles of my Feet, so that I could

neither go or stand for several Days together.

But my good Fortune was my Friend upon this Occasion; for as they were sailing

away with our Ship in Tow as a Prize, steering for the Streights, and in Sight

of the Bay of Cadiz, the Turkish Rover was attack'd by two great Portuguese Men

of War, and taken and carried into Lisbon.

As I was not much concerned at my Captivity, not indeed understanding the

Consequences of it, if it had continued; so I was not suitably sensible of my

Deliverance: Nor indeed was it so much a Deliverance to me, as it would

otherwise ha' been; for my Master, who was the only Friend I had in the World,

died at Lisbon of his Wounds; and I being then almost reduced to my primitive

State, viz. of Starving, had this Addition to it, that it was in a foreign

Country too, where I knew no body, and could not speak

a Word of their Language.

However, I fared better here than I had Reason to expect; for when all the rest

of our Men had their Liberty to go where they would, I that knew not whither to

go, staid in the Ship for several Days, till at length one of the Lieutenants

seeing me, enquired what that young English Dog did there, and why they did not

turn him on Shore?

I heard him, and partly understood what he meant, tho' not what he said, and

began then to be in a terrible Fright; for I knew not where to get a Bit of

Bread; when the Pilot of the Ship, an old Seaman, seeing me look very dull, came

to me, and speaking broken English to me, told me, I must be gone. Whither must

I go (said I?) Where you will, (said he), Home to your own Country, if you will.

How must I go thither (said I?) Why have you no Friend (said he?) No, (said I)

not in the World, but that Dog, pointing to the Ship's Dog, (who having stole a

Piece of Meat just before, had brought it close by me, and I had taken it from

him, and eat it) for he has been a good Friend, and brought me my Dinner.

Well, well, says he, you must have your Dinner; Will you go with me? Yes, says

I, with all my Heart. In short, the old Pilot took me Home with him, and used me

tolerably well, tho' I fared hard enough, and I lived with him about two Years,

during which time he was solliciting his Business, and at length got to be

Master or Pilot under Don Garcia de Pimentesia de Carravallas, Captain of a

Portuguese Gallion, or Carrack, which was bound to Goa in the East-Indies; and

immediately having gotten his Commission, put me on Board to look after his

Cabbin, in which he had stored himself with Abundance of Liquors, Succades,

Sugar, Spices, and other things for his Accommodation in the Voyage, and laid in

afterwards a considerable Quantity of European Goods, fine Lace, and Linnen; and

also Bays, Woollen, Cloath, Stuffs, &c. under the Pretence of his Clothes.

I was too young in the Trade to keep any Journal of this Voyage, tho' my Master,

who was for a Portuguese a pretty good Artist, prompted me to it: But my not

understanding the Language, was one Hindrance; at least, it served me for an

Excuse. However, after some time I began to look into his Charts and Books; and

as I could write a tolerable Hand, understood some Latin, and began to have a

Smattering of the Portuguese Tongue; so I began to get a little superficial

Knowledge of Navigation, but not such as was likely to be sufficient to carry me

thro' a Life of Adventure, as mine was to be. In short, I learnt several

material Things in this Voyage among the Portuguese: I learnt particularly to be

an errant Thief and a bad Sailor; and I think I may say they are the best

Masters for Teaching both these, of any Nation in the World.

We made our Way for the East-Indies, by the Coast of Brasil ; not that it is in

the Course of Sailing the Way thither; but our Captain, either on his own

Account, or by the Direction of the Merchants, went thither first, where at All

Saints Bay, or as they call it in Portugal, the Rio de Todos los Santos, we

delivered near an Hundred Ton of Goods, and took in a considerable Quantity of

Gold, with some Chests of Sugar, and Seventy or Eighty great Rolls of Tobacco,

every Roll weighing at least 100 Weight.

Here being lodged on Shore by my Master's Order, I had the Charge of the

Captain's Business, he having seen me very diligent for my own Master; and in

Requital for his mistaken Confidence, I found Means to secure, that is to say,

to steal about twenty Moydores out of the Gold that was Shipt on Board by the

Merchants, and this was my first Adventure.

We had a tolerable Voyage from hence to the Cape de bona Speranza ; and I was

reputed as a mighty diligent Servant to my Master, and very faithful (I was

diligent indeed, but I was very far from honest; however, they thought me

honest, which by the Way, was their very great Mistake) upon this very Mistake,

the Captain took a particular Liking to me, and employ'd me frequently on his

own Occasions; and on the other Hand, in Recompence for my Officious Diligence,

I received several particular Favours from him; particularly, I was by the

Captain's Command, made a kind of a Steward under the Ship's Steward, for such

Provisions as the Captain demanded for his own Table. He had another Steward for

his private Stores besides, but my Office concerned only what the Captain called

for of the Ship's Stores, for his private Use.

However, by this Means I had Opportunity particularly to take Care of my

Master's Man, and to furnish my self with sufficient Provisions to make me live

much better than the other People in the Ship; for the Captain seldom ordered

any thing out of the Ship's Stores, as above, but I snipt some of it for my own

Share. We arrived at Goa in the East-Indies, in about seven Months, from Lisbon,

and remained there eight more; during which Time I had indeed nothing to do, my

Master being generally on Shore, but to learn every thing that is wicked among

the Portuguese, a Nation the most perfidious and the most debauch'd, the most

insolent and cruel, of any that pretend to call themselves Christians, in the

World.

Thieving, Lying, Swearing, Forswearing, joined to the most abominable Lewdness,

was the stated Practice of the Ship's Crew; adding to it, that with the most

unsufferable Boasts of their new Courage, they were generally speaking the most

compleat Cowards that I ever met with; and the Consequence of their Cowardice

was evident upon many Occasions. However, there was here and there one among

them that was not so bad as the rest; and as my Lot fell among them, it made me

have the most contemptible Thoughts of the rest, as indeed they deserved.

I was exactly fitted for their Society indeed; for I had no Sense of Virtue or

Religion upon me. I had never heard much of either, except what a good old

Parson had said to me when I was a Child of about Eight or Nine Years old; nay,

I was preparing, and growing up apace, to be as wicked as any Body could be, or

perhaps ever was. Fate certainly thus directed my Beginning, knowing that I had

Work which I had to do in the World, which nothing but one hardened against all

Sense of Honesty or Religion, could go thro'; and yet even in this State of

Original Wickedness, I entertained such a settled Abhorrence of the abandon'd

Vileness of the Portuguese, that I could not but hate them most heartily from

the Beginning, and all my Life afterwards. They were so brutishly wicked, so

base and perfidious, not only to Strangers, but to one another; so meanly

submissive when subjected; so insolent, or barbarous and tyrannical when

superiour, that I thought there was something in them that shock'd my very

Nature. Add to this, that 'tis natural to an Englishman to hate a Coward, it all

joined together to make the Devil and a Portuguese equally my Aversion.

However, according to the English Proverb, He that is Shipp'd with the Devil

must sail with the Devil; I was among them, and I manag'd my self as well as I

could. My Master had consented that I should assist the Captain in the Office as

<

br /> above; but as I understood afterwards, that the Captain allowed my Master Half a

Moydore a Month for my Service, and that he had my Name upon the Ship's Books

also, I expected that when the Ship came to be paid four Months Wages at the

Indies, as they it seems always do, my Master would let me have something for my

self.

But I was wrong in my Man, for he was none of that Kind: He had taken me up as

in Distress, and his Business was to keep me so, and make his Market of me as

well as he could; which I began to think of after a different Manner than I did

at first; for at first I thought he had entertained me in meer Charity, upon

seeing my distrest Circumstances, but did not doubt, but when he put me on Board

the Ship, I should have some Wages for my Service.

But he thought, it seems, quite otherwise; and when I procured one to speak to

him about it when the Ship was paid at Goa, he flew into the greatest Rage

imaginable, and called me English Dog, young Heretick, and threaten'd to put me

into the Inquisition. Indeed of all the Names the Four and Twenty Letters could

make up, he should not have called me Heretick; for as I knew nothing about

Religion, neither Protestant from Papist, or either of them from a Mahometan, I

could never be a Heretick. However, it pass'd but a little, but as young as I

was, I had been carried into the Inquisition; and there, if they had ask'd me,

if I was a Protestant or a Catholick, I should have said Yes to that which came

first. If it had been the Protestant they had ask'd first, it had certainly made

a Martyr of me for I did not know what.

But the very Priest they carried with them, or Chaplain of the Ship, as we call

him, saved me; for seeing me a Boy entirely ignorant of Religion, and ready to

do or say any thing they bid me, he ask'd me some Questions about it, which he

found I answered so very simply, that he took it upon him to tell them, he would

answer for my being a good Catholick; and he hoped he should be the Means of

saving my Soul; and he pleased himself, that it was to be a Work of Merit to

him; so he made me as good a Papist as any of them in about a Week's Time.

I then told him my Case about my Master how, it is true, he had taken me up in a

miserable Case, on Board a Man of War at Lisbon ; and I was indebted to him for

bringing me on Board this Ship; that if I had been left at Lisbon, I might have

starv'd, and the like: And therefore I was willing to serve him; but that I

hop'd he would give me some little Consideration for my Service, or let me know

how long he expected I should serve him for nothing.

It was all one; neither the Priest or any one else could prevail with him, but

that I was not his Servant but his Slave; that he took me in the Algerine; and

that I was a Turk, only pretended to be an English Boy, to get my Liberty, and

he would carry me to the Inquisition as a Turk.

This frighted me out of my Wits; for I had no body to vouch for me what I was,

or from whence I came; but the good Padre Antonio, for that was his Name,

cleared me of that Part by a Way I did not understand: For he came to me one

Morning with two Sailors, and told me they must search me, to bear Witness that

I was not a Turk. I was amazed at them, and frighted; and did not understand

them; nor could I imagine what they intended to do to me. However, stripping me,

they were soon satisfy'd; and Father Anthony bad me be easy, for they could all

Witness that I was no Turk. So I escaped that Part of my Master's Cruelty.

And now I resolved from that time to run away from him if I could; but there was

no doing of it there; for there were not Ships of any Nation in the World in

that Port, except two or three Persian Vessels from Ormus; so that if I had

offer'd to go away from him, he would have had me seized on Shore, and brought

on Board by Force. So that I had no Remedy but Patience, and this he brought to

Captain Singleton

Captain Singleton An Essay Upon Projects

An Essay Upon Projects Moll Flanders Moll Flanders Moll Flanders

Moll Flanders Moll Flanders Moll Flanders The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Everybody's Business Is Nobody's Business

Everybody's Business Is Nobody's Business Robinson Crusoe

Robinson Crusoe The Storm

The Storm The King of Pirates

The King of Pirates History of the Plague in London

History of the Plague in London Memoirs of a Cavalier

Memoirs of a Cavalier_preview.jpg) The Life and Most Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner (1801)

The Life and Most Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner (1801) A Journal of the Plague Year

A Journal of the Plague Year_preview.jpg) The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1808)

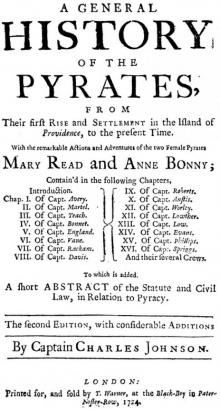

The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1808) A General History of the Pyrates: / from their first rise and settlement in the island of Providence, to the present time

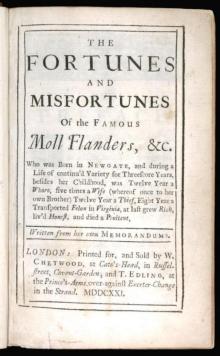

A General History of the Pyrates: / from their first rise and settlement in the island of Providence, to the present time The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders

The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders_preview.jpg) The Fortunate Mistress (Parts 1 and 2)

The Fortunate Mistress (Parts 1 and 2) Robinson Crusoe — in Words of One Syllable

Robinson Crusoe — in Words of One Syllable From London to Land's End

From London to Land's End A New Voyage Round the World by a Course Never Sailed Before

A New Voyage Round the World by a Course Never Sailed Before Roxana

Roxana The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, Volume 1

The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, Volume 1_preview.jpg) Memoirs of Major Alexander Ramkins (1718)

Memoirs of Major Alexander Ramkins (1718) Dickory Cronke

Dickory Cronke Robinson Crusoe (Penguin ed.)

Robinson Crusoe (Penguin ed.) Moll Flanders

Moll Flanders The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe rc-2

The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe rc-2