- Home

- Daniel Defoe

Captain Singleton Page 2

Captain Singleton Read online

Page 2

an End too as soon as he could; for after this he began to use me ill, and not

only to straiten my Provisions, but to beat and torture me in a barbarous Manner

for every Trifle; so that in a Word my Life began to be very miserable.

The Violence of this Usage of me, and the Impossibility of my Escape from his

Hands, set my Head a-working upon all Sorts of Mischief; and in particular, I

resolved, after studying all other Ways to deliver my self, and finding all

ineffectual; I say, I resolved to murther him. With this Hellish Resolution in

my Head, I spent whole Nights and Days contriving how to put it in Execution,

the Devil prompting me very warmly to the Fact. I was indeed entirely at a Loss

for the Means; for I had neither Gun or Sword, nor any Weapon to assault him

with. Poison I had my Thoughts much upon, but knew not where to get any; or if I

might have got it, I did not know the Country Word for it, or by what Name to

ask for it.

In this Manner I quitted the Fact intentionally a Hundred and a Hundred Times;

but Providence, either for his sake, or for mine, always frustrated my Designs,

and I could never bring it to pass; so I was obliged to continue in his Chains

till the Ship, having taken in her Loading, set Sail for Portugal.

I can say nothing here to the Manner of our Voyage; for as I said, I kept no

Journal; but this I can give an Account of, that having been once as high as the

Cape of Good Hope, as we call it; or Cabo de bona Speranza, as they call it, we

were driven back again by a violent Storm from the W. S. W. which held us six

Days and Nights, a great Way to the Eastward; and after that standing afore the

Wind for several Days more, we at last came to an Anchor on the Coast of

Madagascar.

The Storm had been so violent, that the Ship had received a great deal of

Damage, and it required some time to repair her; so standing in nearer the

Shore, the Pilot, My Master, brought the Ship into a very good Harbour, where we

rid in Twenty six Fathom Water, about Half a Mile from the Shore.

While the Ship rode here, there happen'd a most desperate Mutiny among the Men,

upon Account of some Deficiency in their Allowance, which came to that Height,

that they threaten'd the Captain to set him on Shore, and go back with the Ship

to Goa. I wish'd they would, with all my Heart, for I was full of Mischief in my

Head, and ready enough to do any. So, tho' I was but a Boy, as they called me,

yet I prompted the Mischief all I could, and embarked in it so openly, that I

escap'd very little being hang'd in the first and most early Part of my Life;

for the Captain had some Notice, that there was a Design laid by some of the

Company to murther him; and having partly by Money and Promises, and partly by

Threatning and Torture, brought two Fellows to confess the Particulars, and the

Names of the Persons concerned, they were presently apprehended, till one

accusing another, no less than sixteen Men were seized, and put into Irons,

whereof I was one.

The Captain, who was made desperate by his Danger, resolving to clear the Ship

of his Enemies, try'd us all, and we were all condemned to die. The Manner of

his Process I was too young to take Notice of; but the Purser and one of the

Gunners were hang'd immediately, and I expected it with the rest. I do not

remember any great Concern I was under about it, only that I cry'd very much;

for I knew little then of this World, and nothing at all of the next.

However, the Captain contented himself with executing these two; and some of the

rest, upon their hmble Submission, and Promise of future good Behaviour, were

pardoned; but five were ordered to be set on Shore on the Island, and left

there, of which I was one. My Master used all his Interest with the Captain to

have me excused, but could not obtain it; for somebody having told him that I

was one of them, who was singled out to have killed him, when my Master desired

I might not be set on Shore, the Captain told him, I should stay on Board if he

desired it, but then I should be hang'd; so he might chuse for me which he

thought best: The Captain, it seems, was particularly provok'd at my being

concerned in the Treachery, because of his having been so kind to me, and of his

having singled me me out to serve him, as I have said above; and this perhaps

obliged him to give my Master such a rough Choice, either to set me on Shore, or

to have me hang'd on Board: And had my Master indeed known what good Will I had

for him, he would not ha' been long in chusing for me; for I had certainly

determined to do him a Mischief the first Opportunity I had had for it. This was

therefore a good Providence for me, to keep me from dipping my Hands in Blood,

and it made me more tender afterwards in Matters of Blood, than I believe I

should otherwise have been. But as to my being one of them that was to kill the

Captain, that I was wrong'd in, for I was not the Person; but it was really one

of them that were pardoned, he having the good Luck not to have that Part

discovered.

I was now to enter upon a Part of independent Life, a thing I was indeed very

ill prepared to manage; for I was perfectly loose and dissolute in my Behaviour,

bold and wicked while I was under Government, and now perfectly unfit to be

trusted with Liberty; for I was as ripe for any Villainy, as a young Fellow that

had no solid Thought ever placed in his Mind could be supposed to be. Education,

as you have heard, I had none; and all the little Scenes of Life I had pass'd

thro', had been full of Dangers and desperate Circumstances; but I was either so

young, or so stupid, that I escaped the Grief and Anxiety of them, for want of

having a Sense of their Tendency and Consequences.

This thoughtless, unconcern'd Temper had one Felicity indeed in it; that it made

me daring and ready for doing any Mischief, and kept off the Sorrow which

otherwise ought to have attended me when I fell into any Mischief; that this

Stupidity was instead of a Happiness to me, for it left my Thoughts free to act

upon Means of Escape and Deliverance in my Distress, however ever great it might

be; whereas my Companions in the Misery, were so sunk by their Fear and Grief,

that they abandoned themselves to the Misery of their Condition, and gave over

all Thought but of their perishing and starving, being devoured by wild Beasts,

murthered, and perhaps eaten by Cannibals, and the like.

I was but a young Fellow about 17 or 18; but hearing what was to be my Fate, I

received it with no Appearance of Discouragement; but I asked what my Master

said to it, and being told that he had used his utmost Interest to save me, but

the Captain had answered I should either go on Shore or be hanged on Board,

which he pleased; I then gave over all Hope of being received again: I was not

very thankful in my Thoughts to my Master for his solliciting the Captain for

me, because I knew that what he did was not in Kindness to me, so much as in

Kindness to himself; I mean to preserve the Wages which he got for me, which

amounted to above six Dollars a Month, including what the Captain allowed him

for my particular Service to him.

When I understood that my Master was so apparently kind, I asked if I might not

be admitted to speak with him, and they told me I might, if my Master would come

down to me, but I could not be allowed to come up to him; so then I desired my

Master might be spoke to to come to me, and he accordingly came to me; I fell on

my Knees to him, and begg'd he would forgive me what I had done to displease

him; and indeed the Resolution I had taken to murther him, lay with some Horrour

upon my Mind just at that Time, so that I was once just a-going to confess it,

and beg him to forgive me, but I kept it in: He told me he had done all he could

to obtain my Pardon of the Captain, but could not; and he knew no Way for me but

to have Patience, and submit to my Fate; and if they came to speak with any Ship

of their Nation at the Cape, he would endeavour to have them stand in, and fetch

us off again if we might be found.

Then I begg'd I might have my Clothes on Shore with me. He told me he was afraid

I should have little Need of Clothes, for he did not see how we could long

subsist on the Island, and that he had been told that the Inhabitants were

Cannibals or Men-eaters (tho' he had no Reason for that Suggestion) and we

should not be able to live among them. I told him I was not so afraid of that,

as I was of starving for want of Victuals; and as for the Inhabitants being

Cannibals, I believed we should be more likely to eat them, than they us, if we

could but get at them: But I was mightily concerned, I said, we should have no

Weapons with us to defend our selves, and I begg'd nothing now, but that he

would give me a Gun and a Sword, with a little Powder and Shot.

He smiled and said, they would signify nothing to us, for it was impossible for

us to pretend to preserve our Lives among such a populous and desperate Nation

as the People of the Island were. I told him, that however it would do us this

Good, for we should not be devoured or destroy'd immediately; so I begged hard

for the Gun. At last he told me, he did not know whether the Captain would give

him Leave to give me a Gun, and if not, he durst not do it; but he promised to

use his Interest to obtain it forme, which he did, and the next Day he sent me a

Gun, with some Ammunition, but told me, the Captain would not suffer the

Ammunition to be given us, till we were set all on Shore, and till he was just

going to set Sail. He also sent me the few Clothes I had in the Ship, which

indeed were not many.

Two Days after this we were all carried on Shore together; the rest of my

Fellow-Criminals hearing I had a Gun, and some Powder and Shot, sollicited for

Liberty to carry the like with them, which was also granted them; and thus we

were set on Shore to shift for our selves.

At our first coming into the Island, we were terrified exceedingly with the

Sight of the barbarous People; whose Figure was made more terrible to us than

really it was, by the Report we had of them from the Seamen; but when we came to

converse with them a while, we found they were not Cannibals, as was reported,

or such as would fall immediately upon us and eat us up; but they came and sat

down by us, and wondered much at our Clothes and Arms, and made Signs to give us

some Victuals, such as they had, which was only Roots and Plants dug out of the

Ground, for the present, but they brought us Fowls and Flesh afterwards in good

Plenty.

This encouraged the other four Men that were with me very much, for they were

quite dejected before; but now they began to be very familiar with them, and

made Signs, that if they would use us kindly, we would stay and live with them;

which they seemed glad of, tho' they knew little of the Necessity we were under

to do so, or how much we were afraid of them.

However, upon other Thoughts, we resolved that we would only stay in that Part

so long as the Ship rid in the Bay, and then making them believe we were gone

with the Ship, we would go and place our selves, if possible, where there were

no Inhabitants to be seen, and so live as we could, or perhaps watch for a Ship

that might be driven upon the Coast, as we were.

The Ship continued a Fortnight in the Road repairing some Damage which had been

done her in the late Storm, and taking in Wood and Water; and during this time

the Boat coming often on Shore, the Men brought us several Refreshments, and the

Natives believing we only belong'd to the Ship, were civil enough. We lived in a

kind of a Tent on the Shore, or rather a Hut, which we made with the Boughs of

Trees, and sometimes in the Night retired to a Wood a little out of their Way,

to let them think we were gone on board the Ship. However, we found them

barbarous, treacherous, and villainous enough in their Nature, only civil for

Fear, and therefore concluded we should soon fall into their Hands when the Ship

was gone.

The Sense of this wrought upon my Fellow-Sufferers even to Distraction; and one

of them, being a Carpenter, in his mad Fit, swam off to the Ship in the Night,

tho' she lay then a League to Sea, and made such pitiful Moan to be taken in,

that the Captain was prevailed with at last to take him in, tho' they let him

lye swimming three Hours in the Water before he consented to it.

Upon this, and his humble Submission, the Captain received him, and, in a word,

the Importunity of this Man (who for some time petition'd to be taken in, tho'

they hanged him as soon as they had him) was such as could not be resisted; for,

after he had swam so long about the Ship, he was not able to have reached the

Shore again; and the Captain saw evidently that the Man must be taken on Board,

or suffered to drown, and the whole Ship's Company offering to be bound for him

for his good Behaviour, the Captain at last yielded, and he was taken up, but

almost dead with his being so long in the Water.

When this Man was got in, he never left Importuning the Captain and all the rest

of the Officers in Behalf of us that were behind, but to the very last Day the

Captain was inexorable; when, at the time their Preparations were making to

fail, and Orders given to hoist the Boats into the Ship, all the Seamen in a

Body came up to the Rail of the Quarter-Deck, where the Captain was walking with

some of his Officers, and appointing the Boatswain to speak for them, he went

up, and falling on his Knees to the Captain, begged of him in the humblest

manner possible, to receive the four Men on Board again, offering to answer for

their Fidelity, or to have them kept in Chains till they came to Lisbon, and

there to be delivered up to Justice, rather than, as they said, to have them

left to be murthered by Savages, or devoured by wild Beasts. It was a great

while e'er the Captain took any Notice of them, but when he did he ordered the

Boatswain to be seized, and threatned to bring him to the Capstern for speaking

for them.

Upon this Severity, one of the Seamen, bolder than the rest, but still with all

possible Respect to the Captain, besought his Honour, as he called him, that he

would give Leave to some mo

re of them to go on Shore, and die with their

Companions, or, if possible, to assist them to resist the Barbarians. The

Captain, rather provoked than cowd with this, came to the Barricado of the

Quarter-Deck, and speaking very prudently to the Men, (for, had he spoken

roughly, two Thirds of them would have left the Ship, if not all of them) he

told them, it was for their Safety as well as his own, that he had been obliged

to that Severity; that Mutiny on board a Ship was the same thing as Treason in

the King's Palace, and he could not answer it to his Owners and Employers to

trust the Ship and Goods Committed to his Charge, with Men who had entertained

Thoughts of the worst and blackest Nature; that he wished heartily that it had

been any where else that they had been set on Shore, where they might have been

in less Hazard from the Savages; that if he had designed they should be

destroyed, he could as well have executed them on board as the other two; that

he wished it had been in some other Part of the World, where he might have

delivered them up to the Civil Justice, or might have left them among

Christians; but that it was better their Lives were put in Hazard, than his

Life, and the Safety of the Ship; and that tho' he did not know that he had

deserved so ill of any of them, as that they should leave the Ship, rather than

do their Duty; yet if any of them were resolved to do so unless he would consent

to take a Gang of Traytors on board, who, as he had proved before them all, had

conspired to murther him, he would not hinder them, nor, for the present, would

he resent their Importunity; but if there was no body left in the Ship but

himself, he would never consent to take them on board.

This Discourse was delivered so well, was in it self so reasonable, was managed

with so much Temper, yet so boldly concluded with a Negative, that the greatest

Part of the Men were satisfied for the present: However, as it put the Men into

Juncto's and Cabals, and they were not composed for some Hours; the Wind also

slackening towards Night, the Captain ordered not to weigh till next Morning.

The same Night 23 of the Men, among whom was the Gunner's Mate, the Surgeon's

Assistant, and two Carpenters, applying to the Chief Mate, told him, that as the

Captain had given them Leave to go on Shore to their Comerades, they begged,

that he would speak to the Captain not to take it ill that they were desirous to

go and die with their Companions; and that they thought they could do no less in

such an Extremity, than go to them; because if there was any way to save their

Lives, it was by adding to their Numbers, and making them strong enough to

assist one another in defending themselves against the Savages, till perhaps

they might one time or other find Means to make their Escape, and get to their

own Country again.

The Mate told them in so many Words, that he durst not speak to the Captain upon

any such Design, and was very sorry they had no more Respect for him, than to

desire him to go of such an Errand; but if they were resolved upon such an

Enterprize, he would advise them to take the Long-Boat in the Morning betimes,

and go off, seeing the Captain had given them Leave, and leave a civil Letter

behind them to the Captain, and to desire him to send his Men on Shore for the

Boat, which should be delivered very honestly, and he promised to keep their

Counsel so long.

Accordingly an Hour before Day, those 23 Men, with every Man a Fire-lock and

Cutlass, with some Pistols, three Halbards or Half-Pikes, and good Store of

Powder and Ball, without any Provision but about Half an Hundred of Bread, but

with all their Chests and Clothes, Tools, Instruments, Books, &c. embarked

themselves so silently, that the Captain got no Notice of it till they were

gotten half the Way on Shore.

Captain Singleton

Captain Singleton An Essay Upon Projects

An Essay Upon Projects Moll Flanders Moll Flanders Moll Flanders

Moll Flanders Moll Flanders Moll Flanders The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Everybody's Business Is Nobody's Business

Everybody's Business Is Nobody's Business Robinson Crusoe

Robinson Crusoe The Storm

The Storm The King of Pirates

The King of Pirates History of the Plague in London

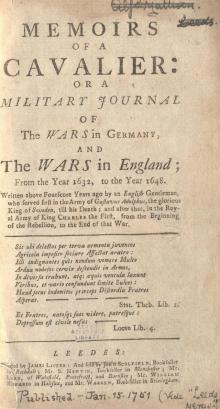

History of the Plague in London Memoirs of a Cavalier

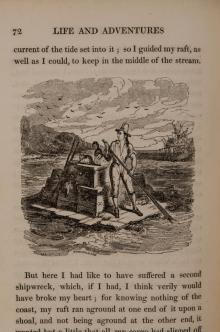

Memoirs of a Cavalier_preview.jpg) The Life and Most Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner (1801)

The Life and Most Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner (1801) A Journal of the Plague Year

A Journal of the Plague Year_preview.jpg) The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1808)

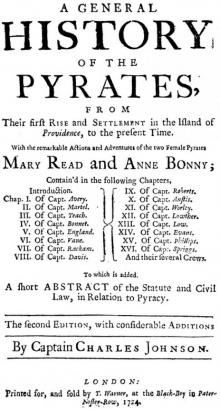

The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1808) A General History of the Pyrates: / from their first rise and settlement in the island of Providence, to the present time

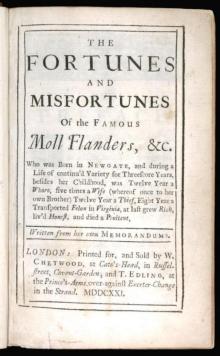

A General History of the Pyrates: / from their first rise and settlement in the island of Providence, to the present time The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders

The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders_preview.jpg) The Fortunate Mistress (Parts 1 and 2)

The Fortunate Mistress (Parts 1 and 2) Robinson Crusoe — in Words of One Syllable

Robinson Crusoe — in Words of One Syllable From London to Land's End

From London to Land's End A New Voyage Round the World by a Course Never Sailed Before

A New Voyage Round the World by a Course Never Sailed Before Roxana

Roxana The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, Volume 1

The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, Volume 1_preview.jpg) Memoirs of Major Alexander Ramkins (1718)

Memoirs of Major Alexander Ramkins (1718) Dickory Cronke

Dickory Cronke Robinson Crusoe (Penguin ed.)

Robinson Crusoe (Penguin ed.) Moll Flanders

Moll Flanders The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe rc-2

The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe rc-2