- Home

- Daniel Defoe

Captain Singleton Page 4

Captain Singleton Read online

Page 4

encouraged when we launched it, and found it swam upright and steady, as we

would have been at another time, if we had a good Man of War at our Command.

She was so very large, that she carried us all very easily, and would have

carried two or three Ton of Baggage with us; so that we began to consult about

going to Sea directly to Goa; but many other Considerations check'd that

Thought, especially when we came to look nearer into it; such as Want of

Provisions, and no Casks for fresh Water; no Compass to steer by; no Shelter

from the Breach of the high Sea, which would certainly founder us; no Defence

from the Heat of the Weather, and the like; so that they all came readily into

my Project, to cruise about where we were, and see what might offer.

Accordingly, to gratify our Fancy, we went one Day all out to Sea in her

together, and we were in a very fair Way to have had enough of it; for when she

had us all on Board, and that we were gotten about Half a League to Sea, there

happening to be a pretty high Swell of the Sea, tho' little or no Wind, yet she

wallow'd so in the Sea, that we all of us thought she would at last wallow her

self Bottom up; so we set all to Work to get her in nearer the Shore, and giving

her fresh Way in the Sea, she swam more steady, and with some hard Work we got

her under the Land again.

We were now at a great Loss; the Natives were civil enough to us, and came often

to discourse with us; one time they brought one whom they shew'd Respect to as a

King, with them, and they set up a long Pole between them and us, with a great

Tossel of Hair hanging, not on the Top, but something above the Middle of it,

adorn'd with little Chains, Shells, Bits of Brass, and the like; and this we

understood afterwards was a Token of Amity and Friendship, and they brought down

to us Victuals in Abundance, Cattel, Fowls, Herbs, Roots, but we were in the

utmost Confusion on our Side; for we had nothing to buy with, or exchange for;

and as to giving us things for nothing, they had no Notion of that again. As to

our Money, it was meer Trash to them, they had no Value for it; so that we were

in a fair Way to be starved. Had we had but some Toys and Trinckets, Brass

Chains, Baubles, Glass Beads, or in a Word, the veriest Trifles that a Ship

Loading would not have been worth the Freight, we might have bought Cattel and

Provisions enough for an Army, or to Victual a Fleet of Men of War, but for Gold

or Silver we could get nothing.

Upon this we were in a strange Consternation. I was but a young Fellow, but I

was for falling upon them with our Fire Arms; and taking all the Cattel from

them, and send them to the Devil to stop their Hunger, rather than be starved

our selves; but I did not consider that this might have brought Ten Thousand of

them down upon us the next Day; and tho' we might have killed a vast Number of

them, and perhaps have frighted the rest, yet their own Desperation, and our

small Number, would have animated them so, that one time or other they would

have destroy'd us all.

In the Middle of our Consultation, one of our Men who had been a kind of a

Cutler, or Worker in Iron, started up, and ask'd the Carpenter, if among all his

Tools he could not help him to a File. Yes, says the Carpenter, I can, but it is

a small one. The smaller the better, says the other. Upon this he goes to Work,

and first by heating a Piece of an old broken Chissel in the Fire, and then with

the Help of his File, he made himself several Kinds of Tools for his Work; and

then he takes three or four Pieces of Eight, and beats them out with a Hammer

upon a Stone, till they were very broad and thin, then he cut them out into the

Shape of Birds and Beasts; he made little Chains of them for Bracelets and

Necklaces, and turn'd them into so many Devices, of his own Head, that it is

hardly to be exprest.

When he had for about a Fortnight exercised his Head and Hands at this Work, we

try'd the Effect of his Ingenuity; and having another Meeting with the Natives,

were surprized to see the Folly of the poor People. For a little Bit of Silver

cut out in the Shape of a Bird, we had two Cows; and, which was our Loss, if it

had been in Brass, it had been still of more Value. For one of the Bracelets

made of Chain-work, we had as much Provision of several Sorts, as would fairly

have been worth in England, Fifteen or Sixteen Pounds; and so of all the rest.

Thus, that which when it was in Coin was not worth Six-pence to us, when thus

converted into Toys and Trifles, was worth an Hundred Times its real Value, and

purchased for us any thing we had Occasion for.

In this Condition, we lived upwards of a Year, but all of us began to be very

much tir'd of it, and whatever came of it, resolv'd to attempt an Escape. We had

furnished our selves with no less than three very good Canoes; and as the

Monsoones, or Trade-Winds, generally affect that Country, blowing in most Parts

of this Island one six Months of a Year one Way, and the other six Months

another Way, we concluded we might be able to bear the Sea well enough. But

always when we came to look nearer into it, the Want of fresh Water was the

thing that put us off from such an Adventure, for it is a prodigious Length, and

what no Man on Earth could be able to perform without Water to drink.

Being thus prevailed upon by our own Reason to set the Thoughts of that Voyage

aside, we had then but two things before us; one was, to put to Sea the other

Way, viz. West, and go away for the Cape of Good Hope, where first or last we

should meet with some of our own Country Ships, or else to put for the main Land

of Africa, and either travel by Land, or sail along the Coast towards the Red

Sea, where we should first or last find a Ship of some Nation or other, that

would take us up, or perhaps we might take them up; which, by the bye, was the

thing that always run in my Head.

It was our ingenious Cutler, whom ever after we called Silver Smith, that

proposed this; but the Gunner told him, that he had been in the Red Sea, in a

Malabar Sloop, and he knew this, that if we went into the Red Sea, we should

either be killed by the wild Arabs, or taken and made Slaves of by the Turks;

and therefore he was not for going that Way.

Upon this I took Occasion to put in my Vote again. Why, said I, do we talk of

being killed by the Arabs, or made Slaves of by the Turks? Are we not able to

board almost any Vessel we shall meet with in those Seas; and instead of their

taking us, we to take them? Well done, Pyrate, said the Gunner, he that had

look'd in my Hand, and told me I should come to the Gallows; I'll say that for

him, says he, he always looks the same Way. But I think o' my Conscience, 'tis

our only Way now. Don't tell me, says I, of being a Pyrate, we must be Pyrates,

or any thing, to get fairly out of this cursed Place.

In a Word, they concluded all by my Advice, that our Business was to cruize for

any thing we could see. Why then, said I to them, our first Business is to see,

if the People upon this Island have no Navigation, and what Boats they use; and

if they have any better

or bigger than ours, let us take one of them. First

indeed all our Aim was to get, if possible, a Boat with a Deck and a Sail; for

then we might have saved our Provisions, which otherwise we could not.

We had, to our great good Fortune, one Sailor among us, who had been Assistant

to the Cook, he told us, that he would find a Way how to preserve our Beef,

without Cask or Pickle; and this he did effectually by curing it in the Sun,

with the Help of Salt-Petre, of which there was great Plenty in the Island; so

that before we found any Method for our Escape, we had dry'd the Flesh of six or

seven Cows and Bullocks, and ten or twelve Goats, and it relished so well, that

we never gave our selves the Trouble to boil it when we eat it, but either

broiled it, or eat it dry: But our main Difficulty about fresh Water still

remained; for we had no Vessel to put any into, much less to keep any for our

going to Sea.

But our first Voyage being only to coast the Island, we resolved to venture,

whatever the Hazard or Consequence of it might be; and in order to preserve as

much fresh Water as we could, our Carpenter made a Well thwart the Middle of one

of our Canoes, which he separated from the other Parts of the Canoe, so as to

make it tight to hold the Water, and cover'd so as we might step upon it; and

this was so large, that it held near a Hogshead of Water very well. I cannot

better describe this Well, than by the same Kind which the small Fisher-Boats in

England have to preserve their Fish alive in; only, that this, instead of having

Holes to let the Salt Water in, was made sound every Way to keep it out; and it

was the first Invention, I believe, of its Kind, for such an Use: But Necessity

is a Spur to Ingenuity, and the Mother of Invention.

It wanted but a little Consultation to resolve now upon our Voyage. The first

Design was only to coast it round the Island, as well to see if we could seize

upon any Vessel fit to embark our selves in, as also to take hold of any

Opportunity which might present for our passing over to the Main; and therefore

our Resolution was to go on the Inside, or West Shore of the Island, where at

least at one Point, the Land stretching a great Way to the North-West, the

Distance is not extraordinary great from the Island to the Coast of Africk.

Such a Voyage, and with such a desperate Crew, I believe was never made; for it

is certain we took the worst Side of the Island to look for any Shipping,

especially for Shipping of other Nations, this being quite out of the Way:

However, we put to Sea, after taking all our Provisions and Ammunition, Bag and

Baggage on Board; we had made both Mast and Sail for our two large Periagua's,

and the other we paddl'd along as well as we could; but when a Gale sprung up,

we took her in Tow.

We sail'd merrily forward for several Days, meeting with nothing to interrupt

us, We saw several of the Natives in small Canoes, catching Fish, and sometimes

we endeavoured to come near enough to speak with them, but they were always

shye, and afraid of us, making in for the Shore, as soon as we attempted it;

till one of our Company remember'd the Signal of Friendship which the Natives

made us from the South Part of the Island, viz. of setting up a long Pole, and

put us in Mind, that perhaps it was the same thing to them as a Flag of Truce

was to us: So we resolved to try it; and accordingly the next time we saw any of

their Fishing Boats at Sea, we put up a Pole in our Canoe that had no Sail, and

rowed towards them. As soon as they saw the Pole, they staid for us, and as we

came nearer, paddl'd towards us. When they came to us, they shewed themselves

very much pleased, and gave us some large Fish, of which we did not know the

Names, bnt they were very good. It was our Misfortune still, that we had nothing

to give them in Return; but our Artist, of whom I spoke before, gave them two

little thin Plates of Silver, beaten, as I said before, out of a Piece of Eight;

they were cut in a Diamond Square, longer one way than t'other, and a Hole

punch'd at one of the longest Corners. This they were so fond of, that they made

us stay till they had cast their Lines and Nets again, and gave us as many Fish

as we cared to have.

All this while we had our Eyes upon their Boats, view'd them very narrowly, and

examined whether any of them were fit for our Turn; but they were poor sorry

things; their Sail was made of a large Matt, only one that was of a Piece of

Cotton Stuff, fit for little, and their Ropes were twisted Flags, of no

Strength; so we concluded we were better as we were, and let them alone. We went

forward to the North, keeping the Coast close on Board for twelve Days together;

and having the Wind at East, and E. S. E. we made very fresh Way. We saw no

Towns on the Shore, but often saw some Hutts by the Water Side, upon the Rocks,

and always Abundance of People about them, who we could perceive run together to

stare at us.

It was as odd a Voyage as ever Men went: We were a little Fleet of three Ships,

and an Army of between Twenty and Thirty as dangerous Fellows as ever they had

among them; and had they known what we were they would have compounded to give

us every thing we desired, to be rid of us.

On the other Hand, we were as miserable as Nature could well make us to be; for

we were upon a Voyage and no Voyage, we were bound some where and no where; for

tho' we knew what we intended to do, we did really not know what we were doing:

We went forward and forward by a Northerly Course; and as we advanced, the Heat

increased, which began to be intolerable to us who were upon the Water, without

any Covering from Heat or Wet; besides we were now in the Month of October, or

thereabouts, in a Southern Latitude, and as we went every Day nearer the Sun,

the Sun came also every Day nearer to us, till at last we found our selves in

the Latitude of 20 Degrees, and having past the Tropick about five or six Days

before that, in a few Days more the Sun would be in the Zenith, just over our

Heads.

Upon these Considerations we resolved to seek for a good Place to go on Shore

again, and pitch our Tents till the Heat of the Weather abated. We had by this

time measured Half the Length of the Island, and were come to that Part where

the Shore tending away to the North-West, promised fair to make our Passage over

to the main Land of Africk, much shorter than we expected. But notwithstanding

that, we had good Reason to believe it was about 120 Leagues.

So, the Heats consider'd, we resolved to take Harbour; besides, our Provisions

were exhausted, and we had not many Days Store left. Accordingly, putting in for

the Shore early in the Morning, as we usually did once in three or four Days,

for fresh Water, we sat down and considered, whether we should go on, or take up

our Standing there; but upon several Considerations too long to repeat here, we

did not like the Place, so we resolved to go on for a few Days longer.

After Sailing on N. W. by N. with a fresh Gale at S. E. about six Days, we found

at a great Distance, a large Promontory, or Cape of Land, pushing ou

t a long Way

into the Sea; and as we were exceeding fond of seeing what was beyond the Cape,

we resolved to double it before we took into Harbour; so we kept on our Way, the

Gale continuing, and yet it was four Days more before we reach'd the Cape. But

it is not possible to express the Discouragement and Melancholy that seized us

all when we came thither; for when we made the Head Land of the Cape, we were

surprized to see the Shore fall away on the other Side, as much as it had

advanced on this Side, and a great deal more; and that, in short, if we would

adventure over to the Shore of Africk, it must be from hence; for that if we

went further, the Breadth of the Sea still increased, and to what Breadth it

might increase, we knew not.

While we mused upon this Discovery, we were surprized with very bad Weather, and

especially violent Rains, with Thunder and Lightning most unusually terrible to

us. In this Pickle we run for the Shore, and getting under the Lee of the Cape,

run our Frigates into a little Creek, where we saw the Land overgrown with

Trees, and made all the Haste possible to get on Shore, being exceeding wet, and

fatigued with the Heat, the Thunder, Lightning and Rain.

Here we though our Case was very deplorable indeed, and therefore our Artist, of

whom I have spoken so often, set up a great Cross of Wood on the Hill, which was

within a Mile of the Head Land, with these Words, but in the Portuguese

Language,

Point Desperation. Jesus have Mercy!

We set to work immediately to build us some Hutts, and so get our Clothes dry'd,

and tho' I was young, and had no Skill in such Things, yet I shall never forget

the little City we built, for it was no less; and we fortify'd it accordingly;

and the Idea is so fresh in my Thought, that I cannot but give a short

Description of it.

Our Camp was on the South Side of a little Creek on the Sea, and under the

Shelter of a steep Hill, which lay, tho' on the other Side of the Creek, yet

within a Quarter of a Mile of us N. W. by N. and very happily intercepted the

Heat of the Sun all the after Part of the Day. The Spot we pitched on had a

little fresh Water, Brook, or a Stream running into the Creek by us, and we saw

Cattle feeding in the Plains and and low Ground, East and to the South of us a

great Way.

Here we set up twelve little Hutts, like Soldiers Tents, but made of the Boughs

of Trees stuck into the Ground, and bound together on the Top with Withes, and

such other things as we could get; the Creek was our Defence on the North, a

little Brook on the West, and the South and East Sides we fortify'd with a Bank,

which entirely covered our Hutts; and being drawn oblique from the North West to

the South East, made our City a Triangle. Behind the Bank, or Line, our Hutts

stood, having three other Hutts behind them at a good Distance. In one of these,

which was a little one, and stood further off, we put our Gun-powder, and

nothing else, for fear of Danger; in the other, which was bigger, we drest our

Victuals, and put all our Necessaries; and in the third, which was biggest of

all, we eat our Dinners, called our Councils, and fat and diverted our selves

with such Conversation as we had one with another, which was but indifferent

truly at that time.

Our Correspondence with the Natives was absolutely necessary, and our Artist,

the Cutler, having made Abundance of those little Diamond cut Squares of Silver,

with these we made Shift to Traffick with the black People for what we wanted;

for indeed they were pleased wonderfully with them: And thus we got Plenty of

Provisions. At first, and in particular, we got about fifty Head of Black Cattel

and Goats, and our Cook's Mate took care to cure them, and dry them, salt and

preserve them for our grand Supply; nor was this hard to do, the Salt and

Captain Singleton

Captain Singleton An Essay Upon Projects

An Essay Upon Projects Moll Flanders Moll Flanders Moll Flanders

Moll Flanders Moll Flanders Moll Flanders The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Everybody's Business Is Nobody's Business

Everybody's Business Is Nobody's Business Robinson Crusoe

Robinson Crusoe The Storm

The Storm The King of Pirates

The King of Pirates History of the Plague in London

History of the Plague in London Memoirs of a Cavalier

Memoirs of a Cavalier_preview.jpg) The Life and Most Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner (1801)

The Life and Most Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner (1801) A Journal of the Plague Year

A Journal of the Plague Year_preview.jpg) The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1808)

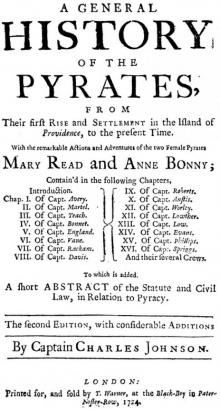

The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1808) A General History of the Pyrates: / from their first rise and settlement in the island of Providence, to the present time

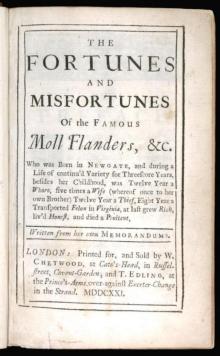

A General History of the Pyrates: / from their first rise and settlement in the island of Providence, to the present time The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders

The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders_preview.jpg) The Fortunate Mistress (Parts 1 and 2)

The Fortunate Mistress (Parts 1 and 2) Robinson Crusoe — in Words of One Syllable

Robinson Crusoe — in Words of One Syllable From London to Land's End

From London to Land's End A New Voyage Round the World by a Course Never Sailed Before

A New Voyage Round the World by a Course Never Sailed Before Roxana

Roxana The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, Volume 1

The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, Volume 1_preview.jpg) Memoirs of Major Alexander Ramkins (1718)

Memoirs of Major Alexander Ramkins (1718) Dickory Cronke

Dickory Cronke Robinson Crusoe (Penguin ed.)

Robinson Crusoe (Penguin ed.) Moll Flanders

Moll Flanders The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe rc-2

The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe rc-2