- Home

- Daniel Defoe

Memoirs of a Cavalier Page 3

Memoirs of a Cavalier Read online

Page 3

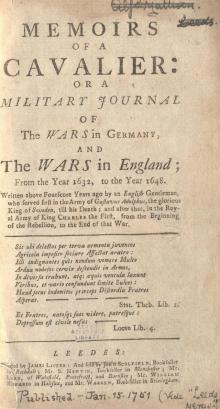

MEMOIRS OF A CAVALIER.

PART I.

It may suffice the reader, without being very inquisitive after myname, that I was born in the county of Salop, in the year 1608, underthe government of what star I was never astrologer enough toexamine; but the consequences of my life may allow me to suppose someextraordinary influence affected my birth.

My father was a gentleman of a very plentiful fortune, having anestate of above L5000 per annum, of a family nearly allied to severalof the principal nobility, and lived about six miles from the town;and my mother being at ---- on some particular occasion, was surprisedthere at a friend's house, and brought me very safe into the world.

I was my father's second son, and therefore was not altogether so muchslighted as younger sons of good families generally are. But my fathersaw something in my genius also which particularly pleased him, and somade him take extraordinary care of my education.

I was taught, therefore, by the best masters that could be had,everything that was needful to accomplish a young gentleman for theworld; and at seventeen years old my tutor told my father an academiceducation was very proper for a person of quality, and he thought mevery fit for it: so my father entered me of ---- College in Oxford,where I continued three years.

A collegiate life did not suit me at all, though I loved books wellenough. It was never designed that I should be either a lawyer,physician, or divine; and I wrote to my father that I thought I hadstayed there long enough for a gentleman, and with his leave I desiredto give him a visit.

During my stay at Oxford, though I passed through the proper exercisesof the house, yet my chief reading was upon history and geography,as that which pleased my mind best, and supplied me with ideas mostsuitable to my genius; by one I understood what great actions had beendone in the world, and by the other I understood where they had beendone.

My father readily complied with my desire of coming home; for besidesthat he thought, as I did, that three years' time at the universitywas enough, he also most passionately loved me, and began to think ofmy settling near him.

At my arrival I found myself extraordinarily caressed by my father,and he seemed to take a particular delight in my conversation. Mymother, who lived in perfect union with him both in desires andaffection, received me very passionately. Apartments were provided forme by myself, and horses and servants allowed me in particular.

My father never went a-hunting, an exercise he was exceeding fond of,but he would have me with him; and it pleased him when he found melike the sport. I lived thus, in all the pleasures 'twas possible forme to enjoy, for about a year more, when going out one morning with myfather to hunt a stag, and having had a very hard chase, and gottena great way off from home, we had leisure enough to ride gently back;and as we returned my father took occasion to enter into a seriousdiscourse with me concerning the manner of my settling in the world.

He told me, with a great deal of passion, that he loved me above allthe rest of his children, and that therefore he intended to do verywell for me; and that my eldest brother being already marriedand settled, he had designed the same for me, and proposed a veryadvantageous match for me, with a young lady of very extraordinaryfortune and merit, and offered to make a settlement of L2000 per annumon me, which he said he would purchase for me without diminishing hispaternal estate.

There was too much tenderness in this discourse not to affect meexceedingly. I told him I would perfectly resign myself unto hisdisposal. But as my father had, together with his love for me, a verynice judgment in his discourse, he fixed his eyes very attentively onme, and though my answer was without the least reserve, yet hethought he saw some uneasiness in me at the proposal, and from thenceconcluded that my compliance was rather an act of discretion thaninclination; and that, however I seemed so absolutely given up to whathe had proposed, yet my answer was really an effect of my obediencerather than my choice.

So he returned very quick upon me: "Look you, son, though I give youmy own thoughts in the matter, yet I would have you be very plain withme; for if your own choice does not agree with mine, I will be youradviser, but will never impose upon you, and therefore let me knowyour mind freely." "I don't reckon myself capable, sir," said I, witha great deal of respect, "to make so good a choice for myself as youcan for me; and though my opinion differed from yours, its being youropinion would reform mine, and my judgment would as readily comply asmy duty." "I gather at least from thence," said my father, "that yourdesigns lay another way before, however they may comply with mine; andtherefore I would know what it was you would have asked of me if I hadnot offered this to you; and you must not deny me your obedience inthis, if you expect I should believe your readiness in the other."

"Sir," said I, "'twas impossible I should lay out for myself justwhat you have proposed; but if my inclinations were never so contrary,though at your command you shall know them, yet I declare them to bewholly subjected to your order. I confess my thoughts did not tendtowards marriage or a settlement; for, though I had no reason toquestion your care of me, yet I thought a gentleman ought always tosee something of the world before he confined himself to any part ofit. And if I had been to ask your consent to anything, it should havebeen to give me leave to travel for a short time, in order to qualifymyself to appear at home like a son to so good a father."

"In what capacity would you travel?" replied my father. "You must goabroad either as a private gentleman, as a scholar, or as a soldier.""If it were in the latter capacity, sir," said I, returning prettyquick, "I hope I should not misbehave myself; but I am not sodetermined as not to be ruled by your judgment." "Truly," replied myfather, "I see no war abroad at this time worth while for a man toappear in, whether we talk of the cause or the encouragement; andindeed, son, I am afraid you need not go far for adventures of thatnature, for times seem to look as if this part of Europe would find uswork enough." My father spake then relating to the quarrel likelyto happen between the King of England and the Spaniard,' [1] for Ibelieve he had no notions of a civil war in his head.

In short, my father, perceiving my inclinations very forward to goabroad, gave me leave to travel, upon condition I would promise toreturn in two years at farthest, or sooner, if he sent for me.

While I was at Oxford I happened into the society of a younggentleman, of a good family, but of a low fortune, being a youngerbrother, and who had indeed instilled into me the first desires ofgoing abroad, and who, I knew, passionately longed to travel, but hadnot sufficient allowance to defray his expenses as a gentleman. Wehad contracted a very close friendship, and our humours being veryagreeable to one another, we daily enjoyed the conversation ofletters. He was of a generous free temper, without the leastaffectation or deceit, a handsome proper person, a strong body, verygood mien, and brave to the last degree. His name was Fielding and wecalled him Captain, though it be a very unusual title in a college;but fate had some hand in the title, for he had certainly the lines ofa soldier drawn in his countenance. I imparted to him the resolutionsI had taken, and how I had my father's consent to go abroad, and wouldknow his mind whether he would go with me. He sent me word he would gowith all his heart.

My father, when he saw him, for I sent for him immediately to cometo me, mightily approved my choice; so we got our equipage ready, andcame away for London.

'Twas on the 22nd of April 1630, when we embarked at Dover, landed ina few hours at Calais, and immediately took post for Paris. I shallnot trouble the reader with a journal of my travels, nor with thedescription of places, which every geographer can do better than I;but these Memoirs being only a relation of what happened either toourselves, or in our own knowledge, I shall confine myself to thatpart of it.

We had indeed some diverting passages in our journey to Paris, asfirst, the horse my comrade was upon fell so very lame with a slipthat he could not go, and hardly stand, and the fellow that rid withus express, pretended to ride away to a town five miles off to get afresh horse, and so left us on the road with one horse between two ofus

. We followed as well as we could, but being strangers, missed theway, and wandered a great way out the road. Whether the man performedin reasonable time or not we could not be sure, but if it had not beenfor an old priest, we had never found him. We met this man, by a verygood accident, near a little village whereof he was curate. We spokeLatin enough just to make him understand us, and he did not speak itmuch better himself; but he carried us into the village to his house,gave us wine and bread, and entertained us with wonderful courtesy.After this he sent into the village, hired a peasant, and a horse formy captain, and sent him to guide us into the road. At parting hemade a great many compliments to us in French, which we could justunderstand; but the sum was, to excuse him for a question he hada mind to ask us. After leave to ask what he pleased, it was if wewanted any money for our journey, and pulled out two pistoles, whichhe offered either to give or lend us.

I mention this exceeding courtesy of the curate because, thoughcivility is very much in use in France, and especially to strangers,yet 'tis a very unusual thing to have them part with their money.

We let the priest know, first, that we did not want money, and nextthat we were very sensible of the obligation he had put upon us; andI told him in particular, if I lived to see him again, I wouldacknowledge it.

This accident of our horse was, as we afterwards found, of some useto us. We had left our two servants behind us at Calais to bring ourbaggage after us, by reason of some dispute between the captain of thepacket and the custom-house officer, which could not be adjusted, andwe were willing to be at Paris. The fellows followed as fast as theycould, and, as near as we could learn, in the time we lost our way,were robbed, and our portmanteaus opened. They took what they pleased;but as there was no money there, but linen and necessaries, the losswas not great.

Our guide carried us to Amiens, where we found the express and our twoservants, who the express meeting on the road with a spare horse, hadbrought back with him thither.

We took this for a good omen of our successful journey, having escapeda danger which might have been greater to us than it was to ourservants; for the highwaymen in France do not always give a travellerthe civility of bidding him stand and deliver his money, butfrequently fire on him first, and then take his money.

We stayed one day at Amiens, to adjust this little disorder, andwalked about the town, and into the great church, but saw nothingvery remarkable there; but going across a broad street near the greatchurch, we saw a crowd of people gazing at a mountebank doctor, whomade a long harangue to them with a thousand antic postures, and gaveout bills this way, and boxes of physic that way, and had a greattrade, when on a sudden the people raised a cry, "_Larron, Larron_!"(in English, "Thief, thief"), on the other side the street, and allthe auditors ran away, from Mr Doctor to see what the matter was.Among the rest we went to see, and the case was plain and shortenough. Two English gentlemen and a Scotchman, travellers as we were,were standing gazing at this prating doctor, and one of them catcheda fellow picking his pocket. The fellow had got some of his money, forhe dropped two or three pieces just by him, and had got hold ofhis watch, but being surprised let it slip again. But the reason oftelling this story is for the management of it. This thief had hisseconds so ready, that as soon as the Englishman had seized him theyfell in, pretended to be mighty zealous for the stranger, takes thefellow by the throat, and makes a great bustle; the gentleman notdoubting but the man was secured let go his own hold of him, and lefthim to them. The hubbub was great, and 'twas these fellows cried,"_Larron, larron_!" but with a dexterity peculiar to themselves hadlet the right fellow go, and pretended to be all upon one of their owngang. At last they bring the man to the gentleman to ask him what thefellow had done, who, when he saw the person they seized on, presentlytold them that was not the man. Then they seemed to be in moreconsternation than before, and spread themselves all over the street,crying, "_Larron, larron_!" pretending to search for the fellow; andso one one way, one another, they were all gone, the noise went over,the gentlemen stood looking one at another, and the bawling doctorbegan to have the crowd about him again. This was the first Frenchtrick I had the opportunity of seeing, but I was told they have agreat many more as dexterous as this.

We soon got acquaintance with these gentlemen, who were going toParis, as well as we; so the next day we made up our company withthem, and were a pretty troop of five gentlemen and four servants.

As we had really no design to stay long at Paris, so indeed, exceptingthe city itself, there was not much to be seen there. CardinalRichelieu, who was not only a supreme minister in the Church, butPrime Minister in the State, was now made also General of the King'sForces, with a title never known in France before nor since, viz.,Lieutenant-General "au place du Roi," in the king's stead, or, as somehave since translated it, representing the person of the king.

Under this character he pretended to execute all the royal powers inthe army without appeal to the king, or without waiting for orders;and having parted from Paris the winter before had now actually begunthe war against the Duke of Savoy, in the process of which he restoredthe Duke of Mantua, and having taken Pignerol from the duke, put itinto such a state of defence as the duke could never force it out ofhis hands, and reduced the duke, rather by manage and conduct thanby force, to make peace without it; so as annexing it to the crown ofFrance it has ever since been a thorn in his foot that has alwaysmade the peace of Savoy lame and precarious, and France has since madePignerol one of the strongest fortresses in the world.

As the cardinal, with all the military part of the court, was in thefield, so the king, to be near him, was gone with the queen and allthe court, just before I reached Paris, to reside at Lyons. All theseconsidered, there was nothing to do at Paris; the court looked like acitizen's house when the family was all gone into the country, andI thought the whole city looked very melancholy, compared to all thefine things I had heard of it.

The queen-mother and her party were chagrined at the cardinal, who,though he owed his grandeur to her immediate favour, was now grown toogreat any longer to be at the command of her Majesty, or indeed in herinterest; and therefore the queen was under dissatisfaction and herparty looked very much down.

The Protestants were everywhere disconsolate, for the losses they hadreceived at Rochelle, Nimes, and Montpelier had reduced them to anabsolute dependence on the king's will, without all possible hopes ofever recovering themselves, or being so much as in a condition totake arms for their religion, and therefore the wisest of them plainlyforesaw their own entire reduction, as it since came to pass. And Iremember very well that a Protestant gentleman told me once, as wewere passing from Orleans to Lyons, that the English had ruined them;and therefore, says he, "I think the next occasion the king takes touse us ill, as I know 'twill not be long before he does, we must allfly over to England, where you are bound to maintain us for havinghelped to turn us out of our own country." I asked him what he meantby saying the English had done it? He returned short upon me: "I donot mean," says he, "by not relieving Rochelle, but by helping to ruinRochelle, when you and the Dutch lent ships to beat our fleet, whichall the ships in France could not have done without you."

I was too young in the world to be very sensible of this before, andtherefore was something startled at the charge; but when I came todiscourse with this gentleman, I soon saw the truth of what he saidwas undeniable, and have since reflected on it with regret, that thenaval power of the Protestants, which was then superior to the royal,would certainly have been the recovery of all their fortunes, had itnot been unhappily broke by their brethren of England and Holland,the former lending seven men-of-war, and the latter twenty, for thedestruction of the Rochellers' fleet; and by these very ships theRochellers' fleet were actually beaten and destroyed, and they neverafterwards recovered their force at sea, and by consequence sunk underthe siege, which the English afterwards in vain attempted to prevent.

These things made the Protestants look very dull, and expected theruin of all their party, whi

ch had certainly happened had the cardinallived a few years longer.

We stayed in Paris, about three weeks, as well to see the court andwhat rarities the place afforded, as by an occasion which had like tohave put a short period to our ramble.

Walking one morning before the gate of the Louvre, with a design tosee the Swiss drawn up, which they always did, and exercised justbefore they relieved the guards, a page came up to me, and speakingEnglish to me, "Sir," says he, "the captain must needs have yourimmediate assistance." I, that had not the knowledge of any personin Paris but my own companion, whom I called captain, had no room toquestion, but it was he that sent for me; and crying out hastily tohim, "Where?" followed the fellow as fast as 'twas possible. He ledme through several passages which I knew not, and at last through atennis-court and into a large room, where three men, like gentlemen,were engaged very briskly two against one. The room was very dark, sothat I could not easily know them asunder, but being fully possessedwith an opinion before of my captain's danger, I ran into the roomwith my sword in my hand. I had not particularly engaged any of them,nor so much as made a pass at any, when I received a very dangerousthrust in my thigh, rather occasioned by my too hasty running in,than a real design of the person; but enraged at the hurt, withoutexamining who it was hurt me, I threw myself upon him, and run mysword quite through his body.

The novelty of the adventure, and the unexpected fall of the man bya stranger come in nobody knew how, had becalmed the other two, thatthey really stood gazing at me. By this time I had discovered that mycaptain was not there, and that 'twas some strange accident broughtme thither. I could speak but little French, and supposed they couldspeak no English, so I stepped to the door to see for the page thatbrought me thither, but seeing nobody there and the passage clear,I made off as fast as I could, without speaking a word; nor did theother two gentlemen offer to stop me.

But I was in a strange confusion when, coming into those entries andpassages which the page led me through, I could by no means find myway out. At last seeing a door open that looked through a house intothe street, I went in, and out at the other door; but then I was atas great a loss to know where I was, and which was the way to mylodgings. The wound in my thigh bled apace, and I could feel the bloodin my breeches. In this interval came by a chair; I called, and wentinto it, and bid them, as well as I could, go to the Louvre; forthough I knew not the name of the street where I lodged, I knew Icould find the way to it when I was at the Bastille. The chairmen wenton their own way, and being stopped by a company of the guards as theywent, set me down till the soldiers were marched by; when looking outI found I was just at my own lodging, and the captain was standing atthe door looking for me. I beckoned him to me, and, whispering, toldhim I was very much hurt, but bid him pay the chairmen, and ask noquestions but come to me.

I made the best of my way upstairs, but had lost so much blood, that Ihad hardly spirits enough to keep me from swooning till he came in.He was equally concerned with me to see me in such a bloody condition,and presently called up our landlord, and he as quickly called in hisneighbours, that I had a room full of people about me in a quarterof an hour. But this had like to have been of worse consequence to methan the other, for by this time there was great inquiring after theperson who killed a man at the tennis-court. My landlord was thensensible of his mistake, and came to me and told me the danger I wasin, and very honestly offered to convey me to a friend's of his, whereI should be very secure; I thanked him, and suffered myself to becarried at midnight whither he pleased. He visited me very often, tillI was well enough to walk about, which was not in less than ten days,and then we thought fit to be gone, so we took post for Orleans. Butwhen I came upon the road I found myself in a new error, for my woundopened again with riding, and I was in a worse condition than before,being forced to take up at a little village on the road, called ----,about ---- miles from Orleans, where there was no surgeon to be had,but a sorry country barber, who nevertheless dressed me as well as hecould, and in about a week more I was able to walk to Orleans at threetimes. Here I stayed till I was quite well, and took coach for Lyonsand so through Savoy into Italy.

I spent nearly two years' time after this bad beginning in travellingthrough Italy, and to the several courts of Rome, Naples, Venice, andVienna.

When I came to Lyons the king was gone from thence to Grenoble to meetthe cardinal, but the queens were both at Lyons.

The French affairs seemed at this time to have but an indifferentaspect. There was no life in anything but where the cardinal was: hepushed on everything with extraordinary conduct, and generally withsuccess; he had taken Susa and Pignerol from the Duke of Savoy, andwas preparing to push the duke even out of all his dominions.

But in the meantime everywhere else things looked ill; the troopswere ill-paid, the magazines empty, the people mutinous, and a generaldisorder seized the minds of the court; and the cardinal, who was thesoul of everything, desired this interview at Grenoble, in order toput things into some better method.

This politic minister always ordered matters so, that if there wassuccess in anything the glory was his, but if things miscarried it wasall laid upon the king. This conduct was so much the more nice, as itis the direct contrary to the custom in like cases, where kings assumethe glory of all the success in an action, and when a thing miscarriesmake themselves easy by sacrificing their ministers and favouritesto the complaints and resentments of the people; but this accuraterefined statesman got over this point.

While we were at Lyons, and as I remember, the third day after ourcoming thither, we had like to have been involved in a state broil,without knowing where we were. It was of a Sunday in the evening, thepeople of Lyons, who had been sorely oppressed in taxes, and the warin Italy pinching their trade, began to be very tumultuous. We foundthe day before the mob got together in great crowds, and talked oddly;the king was everywhere reviled, and spoken disrespectfully of, andthe magistrates of the city either winked at, or durst not attempt tomeddle, lest they should provoke the people.

But on Sunday night, about midnight, we were waked by a prodigiousnoise in the street. I jumped out of bed, and running to the window,I saw the street as full of mob as it could hold, some armed withmuskets and halberds, marched in very good order; others in disorderlycrowds, all shouting and crying out, "Du paix le roi," and the like.One that led a great party of this rabble carried a loaf of bread uponthe top of a pike, and other lesser loaves, signifying the smallnessof their bread, occasioned by dearness.

By morning this crowd was gathered to a great height; they ran rovingover the whole city, shut up all the shops, and forced all thepeople to join with them from thence. They went up to the castle, andrenewing the clamour, a strange consternation seized all the princes.

They broke open the doors of the officers, collectors of the newtaxes, and plundered their houses, and had not the persons themselvesfled in time they had been very ill-treated.

The queen-mother, as she was very much displeased to see suchconsequences of the government, in whose management she had no share,so I suppose she had the less concern upon her. However, she came intothe court of the castle and showed herself to the people, gave moneyamongst them, and spoke gently to them; and by a way peculiar toherself, and which obliged all she talked with, she pacified the mobgradually, sent them home with promises of redress and the like; andso appeased this tumult in two days by her prudence, which the guardsin the castle had small mind to meddle with, and if they had, would inall probability have made the better side the worse.

There had been several seditions of the like nature in sundry otherparts of France, and the very army began to murmur, though not tomutiny, for want of provisions.

This sedition at Lyons was not quite over when we left the place,for, finding the city all in a broil, we considered we had no businessthere, and what the consequence of a popular tumult might be we didnot see, so we prepared to be gone. We had not rid above three milesout of the city but we were brought as prisoners of war

, by a party ofmutineers, who had been abroad upon the scout, and were chargedwith being messengers sent to the cardinal for forces to reduce thecitizens. With these pretences they brought us back in triumph, andthe queen-mother, being by this time grown something familiar to them,they carried us before her.

When they inquired of us who we were, we called ourselves Scots; foras the English were very much out of favour in France at this time,the peace having been made not many months, and not supposed tobe very durable, because particularly displeasing to the people ofEngland, so the Scots were on the other extreme with the French.Nothing was so much caressed as the Scots, and a man had no more todo in France, if he would be well received there, than to say he was aScotchman.

When we came before the queen-mother she seemed to receive us withsome stiffness at first, and caused her guards to take us intocustody; but as she was a lady of most exquisite politics, she didthis to amuse the mob, and we were immediately after dismissed; andthe queen herself made a handsome excuse to us for the rudeness we hadsuffered, alleging the troubles of the times; and the next morning wehad three dragoons of the guards to convoy us out of the jurisdictionof Lyons.

I confess this little adventure gave me an aversion to popular tumultsall my life after, and if nothing else had been in the cause, wouldhave biassed me to espouse the king's party in England when ourpopular heats carried all before it at home.

But I must say, that when I called to mind since, the address, themanagement, the compliance in show, and in general the whole conductof the queen-mother with the mutinous people of Lyons, and compared itwith the conduct of my unhappy master the King of England, I could notbut see that the queen understood much better than King Charles themanagement of politics and the clamours of the people.

Had this princess been at the helm in England, she would haveprevented all the calamities of the Civil War here, and yet not haveparted with what that good prince yielded in order to peace neither.She would have yielded gradually, and then gained upon them gradually;she would have managed them to the point she had designed them, as shedid all parties in France; and none could effectually subject her butthe very man she had raised to be her principal support--I mean thecardinal.

We went from hence to Grenoble, and arrived there the same day thatthe king and the cardinal with the whole court went out to view a bodyof 6000 Swiss foot, which the cardinal had wheedled the cantons togrant to the king to help to ruin their neighbour the Duke of Savoy.

The troops were exceeding fine, well-accoutred, brave, clean-limbed,stout fellows indeed. Here I saw the cardinal; there was an air ofchurch gravity in his habit, but all the vigour of a general, andthe sprightliness of a vast genius in his face. He affected a littlestiffness in his behaviour, but managed all his affairs with suchclearness, such steadiness, and such application, that it was nowonder he had such success in every undertaking.

Here I saw the king, whose figure was mean, his countenance hollow,and always seemed dejected, and every way discovering that weakness inhis countenance that appeared in his actions.

If he was ever sprightly and vigorous it was when the cardinal waswith him, for he depended so much on everything he did, he that was atthe utmost dilemma when he was absent, always timorous, jealous, andirresolute.

After the review the cardinal was absent some days, having been towait on the queen-mother at Lyons, where, as it was discoursed, theywere at least seemingly reconciled.

I observed while the cardinal was gone there was no court, the kingwas seldom to be seen, very small attendance given, and no bustle atthe castle; but as soon as the cardinal returned, the great councilswere assembled, the coaches of the ambassadors went every day to thecastle, and a face of business appeared upon the whole court.

Here the measures of the Duke of Savoy's ruin were concerted, and inorder to it the king and the cardinal put themselves at the headof the army, with which they immediately reduced all Savoy, tookChamberri and the whole duchy except Montmelian.

The army that did this was not above 22,000 men, including the Swiss,and but indifferent troops neither, especially the French foot, who,compared to the infantry I have since seen in the German and Swedisharmies, were not fit to be called soldiers. On the other hand,considering the Savoyards and Italian troops, they were good troops;but the cardinal's conduct made amends for all these deficiencies.

From hence I went to Pignerol, which was then little more than asingle fortification on the hill near the town called St Bride's, butthe situation of that was very strong. I mention this because of theprodigious works since added to it, by which it has since obtained thename of "the right hand of France." They had begun a new line belowthe hill, and some works were marked out on the side of the town nextthe fort; but the cardinal afterwards drew the plan of the works withhis own hand, by which it was made one of the strongest fortresses inEurope.

While I was at Pignerol, the governor of Milan, for the Spaniards,came with an army and sat down before Casale. The grand quarrel,and for which the war in this part of Italy was begun, was this: TheSpaniards and Germans pretended to the duchy of Mantua; the Dukeof Nevers, a Frenchman, had not only a title to it, but had gotpossession of it; but being ill-supported by the French, was beatenout by the Imperialists, and after a long siege the Germans tookMantua itself, and drove the poor duke quite out of the country.

The taking of Mantua elevated the spirits of the Duke of Savoy, andthe Germans and Spaniards being now at more leisure, with a completearmy came to his assistance, and formed the siege of Montferrat.

For as the Spaniards pushed the Duke of Mantua, so the French byway of diversion lay hard upon the Duke of Savoy. They had seizedMontferrat, and held it for the Duke of Mantua, and had a strongFrench garrison under Thoiras, a brave and experienced commander; andthus affairs stood when we came into the French army.

I had no business there as a soldier, but having passed as a Scotchgentleman with the mob at Lyons, and after with her Majesty thequeen-mother, when we obtained the guard of her dragoons, we had alsoher Majesty's pass, with which we came and went where we pleased. Andthe cardinal, who was then not on very good terms with the queen, butwilling to keep smooth water there, when two or three times our passescame to be examined, showed a more than ordinary respect to us on thatvery account, our passes being from the queen.

Casale being besieged, as I have observed, began to be in danger, forthe cardinal, who 'twas thought had formed a design to ruin Savoy, wasmore intent upon that than upon the succour of the Duke of Mantua; butnecessity calling upon him to deliver so great a captain as Thoiras,and not to let such a place as Casale fall into the hands of theenemy, the king, or cardinal rather, ordered the Duke of Montmorency,and the Marechal D'Effiat, with 10,000 foot and 2000 horse, to marchand join the Marechals De La Force and Schomberg, who lay already withan army on the frontiers of Genoa, but too weak to attempt the raisingthe siege of Casale.

As all men thought there would be a battle between the French and theSpaniards, I could not prevail with myself to lose the opportunity,and therefore by the help of the passes above mentioned, I came tothe French army under the Duke of Montmorency. We marched through theenemy's country with great boldness and no small hazard, for the Dukeof Savoy appeared frequently with great bodies of horse on the rear ofthe army, and frequently skirmished with our troops, in one of whichI had the folly--I can call it no better, for I had no businessthere--to go out and see the sport, as the French gentlemen called it.I was but a raw soldier, and did not like the sport at all, for thisparty was surrounded by the Duke of Savoy, and almost all killed, foras to quarter they neither asked nor gave. I ran away very fairly,one of the first, and my companion with me, and by the goodness of ourhorses got out of the fray, and being not much known in the army, wecame into the camp an hour or two after, as if we had been only ridingabroad for the air.

This little rout made the general very cautious, for the Savoyardswere stronger in horse by three or four thousand, and the army alwaysmarched in a bod

y, and kept their parties in or very near hand.

I escaped another rub in this French army about five days after, whichhad like to have made me pay dear for my curiosity.

The Duke de Montmorency and the Marechal Schomberg joined their armyabout four or five days after, and immediately, according to thecardinal's instructions, put themselves on the march for the relief ofCasale.

The army had marched over a great plain, with some marshy groundson the right and the Po on the left, and as the country was so welldiscovered that 'twas thought impossible any mischief should happen,the generals observed the less caution. At the end of this plain was along wood and a lane or narrow defile through the middle of it.

Through this pass the army was to march, and the van began to filethrough it about four o'clock. By three hours' time all the army wasgot through, or into the pass, and the artillery was just enteredwhen the Duke of Savoy with 4000 horse and 1500 dragoons with everyhorseman a footman behind him, whether he had swam the Po or passed itabove at a bridge, and made a long march after, was not examined, buthe came boldly up the plain and charged our rear with a great deal offury.

Our artillery was in the lane, and as it was impossible to turn themabout and make way for the army, so the rear was obliged to supportthemselves and maintain the fight for above an hour and a half.

In this time we lost abundance of men, and if it had not been for twoaccidents all that line had been cut off. One was, that the wood wasso near that those regiments which were disordered presently shelteredthemselves in the wood; the other was, that by this time the MarechalSchomberg, with the horse of the van, began to get back through thelane, and to make good the ground from whence the other had beenbeaten, till at last by this means it came to almost a pitched battle.

There were two regiments of French dragoons who did excellent servicein this action, and maintained their ground till they were almost allkilled.

Had the Duke of Savoy contented himself with the defeat of fiveregiments on the right, which he quite broke and drove into the wood,and with the slaughter and havoc which he had made among the rest,he had come off with honour, and might have called it a victory; butendeavouring to break the whole party and carry off some cannon, theobstinate resistance of these few dragoons lost him his advantages,and held him in play till so many fresh troops got through the passagain as made us too strong for him, and had not night parted them hehad been entirely defeated.

At last, finding our troops increase and spread themselves on hisflank, he retired and gave over. We had no great stomach to pursue himneither, though some horse were ordered to follow a little way.

The duke lost about a thousand men, and we almost twice as many, andbut for those dragoons had lost the whole rear-guard and half ourcannon. I was in a very sorry case in this action too. I was with therear in the regiment of horse of Perigoort, with a captain of whichregiment I had contracted some acquaintance. I would have rid off atfirst, as the captain desired me, but there was no doing it, for thecannon was in the lane, and the horse and dragoons of the van eagerlypressing back through the lane must have run me down or carried mewith them. As for the wood, it was a good shelter to save one's life,but was so thick there was no passing it on horseback.

Our regiment was one of the first that was broke, and being all inconfusion, with the Duke of Savoy's men at our heels, away we ran intothe wood. Never was there so much disorder among a parcel of runawaysas when we came to this wood; it was so exceeding bushy and thick atthe bottom there was no entering it, and a volley of small shot froma regiment of Savoy's dragoons poured in upon us at our breaking intothe wood made terrible work among our horses.

For my part I was got into the wood, but was forced to quit my horse,and by that means, with a great deal of difficulty, got a littlefarther in, where there was a little open place, and being quite spentwith labouring among the bushes I sat down resolving to take my fatethere, let it be what it would, for I was not able to go any farther.I had twenty or thirty more in the same condition come to me in lessthan half-an-hour, and here we waited very securely the success of thebattle, which was as before.

It was no small relief to those with me to hear the Savoyards werebeaten, for otherwise they had all been lost; as for me, I confess,I was glad as it was because of the danger, but otherwise I cared notmuch which had the better, for I designed no service among them.

One kindness it did me, that I began to consider what I had to dohere, and as I could give but a very slender account of myself forwhat it was I run all these risks, so I resolved they should fight itamong themselves, for I would come among them no more.

The captain with whom, as I noted above, I had contracted someacquaintance in this regiment, was killed in this action, and theFrench had really a great blow here, though they took care to concealit all they could; and I cannot, without smiling, read some of thehistories and memoirs of this action, which they are not ashamed tocall a victory.

We marched on to Saluzzo, and the next day the Duke of Savoy presentedhimself in battalia on the other side of a small river, giving us afair challenge to pass and engage him. We always said in our camp thatthe orders were to fight the Duke of Savoy wherever we met him; butthough he braved us in our view we did not care to engage him, but webrought Saluzzo to surrender upon articles, which the duke could notrelieve without attacking our camp, which he did not care to do.

The next morning we had news of the surrender of Mantua to theImperial army. We heard of it first from the Duke of Savoy's cannon,which he fired by way of rejoicing, and which seemed to make himamends for the loss of Saluzzo.

As this was a mortification to the French, so it quite damped thesuccess of the campaign, for the Duke de Montmorency imagining thatthe Imperial general would send immediate assistance to the MarquisSpinola, who besieged Casale, they called frequent councils of warwhat course to take, and at last resolved to halt in Piedmont. A fewdays after their resolutions were changed again by the news of thedeath of the Duke of Savoy, Charles Emanuel, who died, as some say,agitated with the extremes of joy and grief.

This put our generals upon considering again whether they should marchto the relief of Casale, but the chimera of the Germans put them by,and so they took up quarters in Piedmont. They took several smallplaces from the Duke of Savoy, making advantage of the consternationthe duke's subjects were in on the death of their prince, and spreadthemselves from the seaside to the banks of the Po. But here an enemydid that for them which the Savoyards could not, for the plague gotinto their quarters and destroyed abundance of people, both of thearmy and of the country.

I thought then it was time for me to be gone, for I had no manner ofcourage for that risk; and I think verily I was more afraid of beingtaken sick in a strange country than ever I was of being killed inbattle. Upon this resolution I procured a pass to go for Genoa, andaccordingly began my journey, but was arrested at Villa Franca by aslow lingering fever, which held me about five days, and then turnedto a burning malignancy, and at last to the plague. My friend, thecaptain, never left me night nor day; and though for four days more Iknew nobody, nor was capable of so much as thinking of myself, yet itpleased God that the distemper gathered in my neck, swelled and broke.During the swelling I was raging mad with the violence of pain, whichbeing so near my head swelled that also in proportion, that my eyeswere swelled up, and for the twenty-four hours my tongue and mouth;then, as my servant told me, all the physicians gave me over, as pastall remedy, but by the good providence of God the swelling broke.

The prodigious collection of matter which this swelling dischargedgave me immediate relief, and I became sensible in less than an hour'stime; and in two hours or thereabouts fell into a little slumber whichrecovered my spirits and sensibly revived me. Here I lay by it tillthe middle of September. My captain fell sick after me, but recoveredquickly. His man had the plague, and died in two days; my man held itout well.

About the middle of September we heard of a truce concluded betweenall parties, and being u

nwilling to winter at Villa Franca, I gotpasses, and though we were both but weak, we began to travel inlitters for Milan.

And here I experienced the truth of an old English proverb, thatstanders-by see more than the gamesters.

The French, Savoyards, and Spaniards made this peace or truce all forseparate and several grounds, and every one were mistaken.

The French yielded to it because they had given over the relief ofCasale, and were very much afraid it would fall into the hands of theMarquis Spinola. The Savoyards yielded to it because they were afraidthe French would winter in Piedmont; the Spaniards yielded to itbecause the Duke of Savoy being dead, and the Count de Colalto, theImperial general, giving no assistance, and his army weakened bysickness and the fatigues of the siege, he foresaw he should nevertake the town, and wanted but to come off with honour.

The French were mistaken, because really Spinola was so weak that hadthey marched on into Montferrat the Spaniards must have raised thesiege; the Duke of Savoy was mistaken, because the plague had soweakened the French that they durst not have stayed to winter inPiedmont; and Spinola was mistaken, for though he was very slow, if hehad stayed before the town one fortnight longer, Thoiras the governormust have surrendered, being brought to the last extremity.

Of all these mistakes the French had the advantage, for Casale, wasrelieved, the army had time to be recruited, and the French had thebest of it by an early campaign.

I passed through Montferrat in my way to Milan just as the truce wasdeclared, and saw the miserable remains of the Spanish army, who bysickness, fatigue, hard duty, the sallies of the garrison and suchlike consequences, were reduced to less than 2000 men, and of themabove 1000 lay wounded and sick in the camp.

Here were several regiments which I saw drawn out to their arms thatcould not make up above seventy or eighty men, officers and all, andthose half starved with hunger, almost naked, and in a lamentablecondition. From thence I went into the town, and there things werestill in a worse condition, the houses beaten down, the walls andworks ruined, the garrison, by continual duty, reduced from 4500 mento less than 800, without clothes, money, or provisions, the bravegovernor weak with continual fatigue, and the whole face of things ina miserable case.

The French generals had just sent them 30,000 crowns for presentsupply, which heartened them a little, but had not the truce been madeas it was, they must have surrendered upon what terms the Spaniardshad pleased to make them.

Never were two armies in such fear of one another with so littlecause; the Spaniards afraid of the French whom the plague haddevoured, and the French afraid of the Spaniards whom the siege hadalmost ruined.

The grief of this mistake, together with the sense of his master,the Spaniards, leaving him without supplies to complete the siege ofCasale, so affected the Marquis Spinola, that he died for grief, andin him fell the last of that rare breed of Low Country soldiers, whogave the world so great and just a character of the Spanish infantry,as the best soldiers of the world; a character which we see them sovery much degenerated from since, that they hardly deserve the name ofsoldiers.

I tarried at Milan the rest of the winter, both for the recovery of myhealth, and also for supplies from England.

Here it was I first heard the name of Gustavus Adolphus, the king ofSweden, who now began his war with the emperor; and while the kingof France was at Lyons, the league with Sweden was made, in which theFrench contributed 1,200,000 crowns in money, and 600,000 per annumto the attempt of Gustavus Adolphus. About this time he landed inPomerania, took the towns of Stettin and Stralsund, and from thenceproceeded in that prodigious manner of which I shall have occasion tobe very particular in the prosecution of these Memoirs.

I had indeed no thoughts of seeing that king or his armies. I hadbeen so roughly handled already, that I had given over the thoughtsof appearing among the fighting people, and resolved in the springto pursue my journey to Venice, and so for the rest of Italy. YetI cannot deny that as every Gazette gave us some accounts of theconquests and victories of this glorious prince, it prepossessed mythoughts with secret wishes of seeing him, but these were so youngand unsettled, that I drew no resolutions from them for a long whileafter.

About the middle of January I left Milan and came to Genoa, fromthence by sea to Leghorn, then to Naples, Rome, and Venice, but sawnothing in Italy that gave me any diversion.

As for what is modern, I saw nothing but lewdness, private murders,stabbing men at the corner of a street, or in the dark, hiring ofbravos, and the like. These were to me the modern excellencies ofItaly; and I had no gust to antiquities.

'Twas pleasant indeed when I was at Rome to say here stood theCapitol, there the Colossus of Nero, here was the Amphitheatre ofTitus, there the Aqueduct of----, here the Forum, there the Catacombs,here the Temple of Venus, there of Jupiter, here the Pantheon, and thelike; but I never designed to write a book. As much as was useful Ikept in my head, and for the rest, I left it to others.

I observed the people degenerated from the ancient gloriousinhabitants, who were generous, brave, and the most valiant of allnations, to a vicious baseness of soul, barbarous, treacherous,jealous and revengeful, lewd and cowardly, intolerably proud andhaughty, bigoted to blind, incoherent devotion, and the grossest ofidolatry.

Indeed, I think the unsuitableness of the people made the placeunpleasant to me, for there is so little in a country to recommend itwhen the people disgrace it, that no beauties of the creation can makeup for the want of those excellencies which suitable society procurethe defect of. This made Italy a very unpleasant country to me;the people were the foil to the place, all manner of hateful vicesreigning in their general way of living.

I confess I was not very religious myself, and being come abroad intothe world young enough, might easily have been drawn into evils thathad recommended themselves with any tolerable agreeableness to natureand common manners; but when wickedness presented itself full-grown inits grossest freedoms and liberties, it quite took away all the gustto vice that the devil had furnished me with.

The prodigious stupid bigotry of the people also was irksome to me; Ithought there was something in it very sordid. The entire empire thepriests have over both the souls and bodies of the people, gave me aspecimen of that meanness of spirit, which is nowhere else to be seenbut in Italy, especially in the city of Rome.

At Venice I perceived it quite different, the civil authority havinga visible superiority over the ecclesiastic, and the Church being moresubject there to the State than in any other part of Italy.

For these reasons I took no pleasure in filling my memoirs of Italywith remarks of places or things. All the antiquities and valuableremains of the Roman nation are done better than I can pretend to bysuch people who made it more their business; as for me, I went to see,and not to write, and as little thought then of these Memoirs as I illfurnished myself to write them.

I left Italy in April, and taking the tour of Bavaria, though verymuch out of the way, I passed through Munich, Passau, Lintz, and atlast to Vienna.

I came to Vienna the 10th of April 1631, intending to have gone fromthence down the Danube into Hungary, and by means of a pass, which Ihad obtained from the English ambassador at Constantinople, I designedto have seen all the great towns on the Danube, which were then in thehands of the Turks, and which I had read much of in the history ofthe war between the Turks and the Germans; but I was diverted from mydesign by the following occasion.

There had been a long bloody war in the empire of Germany for twelveyears, between the emperor, the Duke of Bavaria, the King ofSpain, and the Popish princes and electors on the one side, and theProtestant princes on the other; and both sides having been exhaustedby the war, and even the Catholics themselves beginning to dislike thegrowing power of the house of Austria, 'twas thought all parties werewilling to make peace. Nay, things were brought to that pass that someof the Popish princes and electors began to talk of making allianceswith the King of Sweden.

Here it is necessary to obs

erve, that the two Dukes of Mecklenburghaving been dispossessed of most of their dominions by the tyrannyof the Emperor Ferdinand, and being in danger of losing the rest,earnestly solicited the King of Sweden to come to their assistance;and that prince, as he was related to the house of Mecklenburg, andespecially as he was willing to lay hold of any opportunity to breakwith the emperor, against whom he had laid up an implacable prejudice,was very ready and forward to come to their assistance.

The reasons of his quarrel with the emperor were grounded upon theImperialists concerning themselves in the war of Poland, where theemperor had sent 8000 foot and 2000 horse to join the Polish armyagainst the king, and had thereby given some check to his arms in thatwar.

In pursuance, therefore, of his resolution to quarrel with theemperor, but more particularly at the instances of the princesabove-named, his Swedish Majesty had landed the year before atStralsund with about 12,000 men, and having joined with some forceswhich he had left in Polish Prussia, all which did not make 30,000men, he began a war with the emperor, the greatest in event, filledwith the most famous battles, sieges, and extraordinary actions,including its wonderful success and happy conclusion, of any war evermaintained in the world.

The King of Sweden had already taken Stettin, Stralsund, Rostock,Wismar, and all the strong places on the Baltic, and began to spreadhimself in Germany. He had made a league with the French, as Iobserved in my story of Saxony; he had now made a treaty with the Dukeof Brandenburg, and, in short, began to be terrible to the empire.

In this conjuncture the emperor called the General Diet of the empireto be held at Ratisbon, where, as was pretended, all sides wereto treat of peace and to join forces to beat the Swedes out of theempire. Here the emperor, by a most exquisite management, brought theaffairs of the Diet to a conclusion, exceedingly to his own advantage,and to the farther oppression of the Protestants; and, in particular,in that the war against the King of Sweden was to be carried on insuch manner as that the whole burden and charge would lie on theProtestants themselves, and they be made the instruments to opposetheir best friends. Other matters also ended equally to theirdisadvantage, as the methods resolved on to recover the Church lands,and to prevent the education of the Protestant clergy; and whatremained was referred to another General Diet to be held atFrankfort-au-Main in August 1631.

I won't pretend to say the other Protestant princes of Germany hadnever made any overtures to the King of Sweden to come to theirassistance, but 'tis plain they had entered into no league with him;that appears from the difficulties which retarded the fixing of thetreaties afterward, both with the Dukes of Brandenburg and Saxony,which unhappily occasioned the ruin of Magdeburg.

But 'tis plain the Swede was resolved on a war with the emperor. HisSwedish majesty might, and indeed could not but foresee that if heonce showed himself with a sufficient force on the frontiers of theempire, all the Protestant princes would be obliged by their interestor by his arms to fall in with him, and this the consequence madeappear to be a just conclusion, for the Electors of Brandenburg andSaxony were both forced to join with him.

First, they were willing to join with him--at least they could notfind in their hearts to join with the emperor, of whose power theyhad such just apprehensions. They wished the Swedes success, and wouldhave been very glad to have had the work done at another man's charge,but, like true Germans, they were more willing to be saved than tosave themselves, and therefore hung back and stood upon terms.

Secondly, they were at last forced to it. The first was forced to joinby the King of Sweden himself, who being come so far was not to bedallied with, and had not the Duke of Brandenburg complied as he did,he had been ruined by the Swede. The Saxon was driven into the armsof the Swede by force, for Count Tilly, ravaging his country, made himcomply with any terms to be saved from destruction.

Thus matters stood at the end of the Diet at Ratisbon. The Kingof Sweden began to see himself leagued against at the Diet both byProtestant and Papist; and, as I have often heard his Majesty saysince, he had resolved to try to force them off from the emperor, andto treat them as enemies equally with the rest if they did not.

But the Protestants convinced him soon after, that though theywere tricked into the outward appearance of a league against him atRatisbon, they had no such intentions; and by their ambassadors to himlet him know that they only wanted his powerful assistance to defendtheir councils, when they would soon convince him that they had a duesense of the emperor's designs, and would do their utmost for theirliberty. And these I take to be the first invitations the King ofSweden had to undertake the Protestant cause as such, and whichentitled him to say he fought for the liberty and religion of theGerman nation.

I have had some particular opportunities to hear these things form themouths of some of the very princes themselves, and therefore am theforwarder to relate them; and I place them here because, previousto the part I acted on this bloody scene, 'tis necessary to let thereader into some part of that story, and to show him in what mannerand on what occasions this terrible war began.

The Protestants, alarmed at the usage they had met with at the formerDiet, had secretly proposed among themselves to form a general unionor confederacy, for preventing that ruin which they saw, unless somespeedy remedies were applied, would be inevitable. The Elector ofSaxony, the head of the Protestants, a vigorous and politic prince,was the first that moved it; and the Landgrave of Hesse, a zealous andgallant prince, being consulted with, it rested a great while betweenthose two, no method being found practicable to bring it to pass, theemperor being so powerful in all parts, that they foresaw the pettyprinces would not dare to negotiate an affair of such a nature,being surrounded with the Imperial forces, who by their two generals,Wallenstein and Tilly, kept them in continual subjection and terror.

This dilemma had like to have stifled the thoughts of the union asa thing impracticable, when one Seigensius, a Lutheran minister, aperson of great abilities, and one whom the Elector of Saxony madegreat use of in matters of policy as well as religion, contrived forthem this excellent expedient.

I had the honour to be acquainted with this gentleman while I was atLeipsic. It pleased him exceedingly to have been the contriver of sofine a structure as the Conclusions of Leipsic, and he was glad to beentertained on that subject. I had the relation from his own mouth,when, but very modestly, he told me he thought 'twas an inspirationdarted on a sudden into his thoughts, when the Duke of Saxony callinghim into his closet one morning, with a face full of concern, shakinghis head, and looking very earnestly, "What will become of us,doctor?" said the duke; "we shall all be undone at Frankfort-au-Main.""Why so, please your highness?" says the doctor. "Why, they will fightwith the King of Sweden with our armies and our money," says the duke,"and devour our friends and ourselves by the help of our friends andourselves." "But what is become of the confederacy, then," said thedoctor, "which your highness had so happily framed in your thoughts,and which the Landgrave of Hesse was so pleased with?" "Become of it?"says the duke, "'tis a good thought enough, but 'tis impossible tobring it to pass among so many members of the Protestant princes asare to be consulted with, for we neither have time to treat, nor willhalf of them dare to negotiate the matter, the Imperialists beingquartered in their very bowels." "But may not some expedient be foundout," says the doctor, "to bring them all together to treat of it ina general meeting?" "'Tis well proposed," says the duke, "but in whattown or city shall they assemble where the very deputies shall notbe besieged by Tilly or Wallenstein in fourteen days' time, andsacrificed to the cruelty and fury of the Emperor Ferdinand?" "Willyour highness be the easier in it," replies the doctor, "if a way maybe found out to call such an assembly upon other causes, at which theemperor may have no umbrage, and perhaps give his assent? You know theDiet at Frankfort is at hand; 'tis necessary the Protestants shouldhave an assembly of their own to prepare matters for the General Diet,and it may be no difficult matter to obtain it." The duke, surprisedwith joy at the motion, embraced the doctor wi

th an extraordinarytransport. "Thou hast done it, doctor," said he, and immediatelycaused him to draw a form of a letter to the emperor, which he didwith the utmost dexterity of style, in which he was a great master,representing to his Imperial Majesty that, in order to put an end tothe troubles of Germany, his Majesty would be pleased to permit theProtestant princes of the empire to hold a Diet to themselves, toconsider of such matters as they were to treat of at the GeneralDiet, in order to conform themselves to the will and pleasure of hisImperial Majesty, to drive out foreigners, and settle a lasting peacein the empire. He also insinuated something of their resolutionsunanimously to give their suffrages in favour of the King of Hungaryat the election of a king of the Romans, a thing which he knew theemperor had in his thought, and would push at with all his might atthe Diet. This letter was sent, and the bait so neatly concealed, thatthe Electors of Bavaria and Mentz, the King of Hungary, and severalof the Popish princes, not foreseeing that the ruin of them all lay inthe bottom of it, foolishly advised the emperor to consent to it.

In consenting to this the emperor signed his own destruction, for herebegan the conjunction of the German Protestants with the Swede, whichwas the fatalest blow to Ferdinand, and which he could never recover.

Accordingly the Diet was held at Leipsic, February 8, 1630, where theProtestants agreed on several heads for their mutual defence,which were the grounds of the following war. These were the famousConclusions of Leipsic, which so alarmed the emperor and the wholeempire, that to crush it in the beginning, the emperor commanded CountTilly immediately to fall upon the Landgrave of Hesse and the Duke ofSaxony as the principal heads of the union; but it was too late.

The Conclusions were digested into ten heads:--

1. That since their sins had brought God's judgments upon the wholeProtestant Church, they should command public prayers to be made toAlmighty God for the diverting the calamities that attended them.

2. That a treaty of peace might be set on foot, in order to come to aright understanding with the Catholic princes.

3. That a time for such a treaty being obtained, they should appointan assembly of delegates to meet preparatory to the treaty.

4. That all their complaints should be humbly represented to hisImperial Majesty and the Catholic Electors, in order to a peaceableaccommodation.

5. That they claim the protection of the emperor, according to thelaws of the empire, and the present emperor's solemn oath and promise.

6. That they would appoint deputies who should meet at certaintimes to consult of their common interest, and who should be alwaysempowered to conclude of what should be thought needful for theirsafety.

7. That they will raise a competent force to maintain and defend theirliberties, rights, and religion.

8. That it is agreeable to the Constitution of the empire, concludedin the Diet at Augsburg, to do so.

9. That the arming for their necessary defence shall by no meanshinder their obedience to his Imperial Majesty, but that they willstill continue their loyalty to him.

10. They agree to proportion their forces, which in all amounted to70,000 men.

The emperor, exceedingly startled at the Conclusions, issued out asevere proclamation or ban against them, which imported much thesame thing as a declaration of war, and commanded Tilly to begin,and immediately to fall on the Duke of Saxony with all the furyimaginable, as I have already observed.

Here began the flame to break out; for upon the emperor's ban, theProtestants send away to the King of Sweden for succour.

His Swedish Majesty had already conquered Mecklenburg, and part ofPomerania, and was advancing with his victorious troops, increasedby the addition of some regiments raised in those parts, in order tocarry on the war against the emperor, having designed to follow upthe Oder into Silesia, and so to push the war home to the emperor'shereditary countries of Austria and Bohemia, when the first messengerscame to him in this case; but this changed his measures, and broughthim to the frontiers of Brandenburg resolved to answer the desiresof the Protestants. But here the Duke of Brandenburg began to halt,making some difficulties and demanding terms, which drove the king touse some extremities with him, and stopped the Swedes for a while,who had otherwise been on the banks of the Elbe as soon as Tilly,the Imperial general, had entered Saxony, which if they had done, themiserable destruction of Magdeburg had been prevented, as I observedbefore. The king had been invited into the union, and when he firstcame back from the banks of the Oder he had accepted it, and waspreparing to back it with all his power.

The Duke of Saxony had already a good army which he had with infinitediligence recruited, and mustered them under the cannon of Leipsic.The King of Sweden having, by his ambassador at Leipsic, entered intothe union of the Protestants, was advancing victoriously to their aid,just as Count Tilly had entered the Duke of Saxony's dominions. Thefame of the Swedish conquests, and of the hero who commanded them,shook my resolution of travelling into Turkey, being resolved to seethe conjunction of the Protestant armies, and before the fire wasbroke out too far to take the advantage of seeing both sides.

While I remained at Vienna, uncertain which way I should proceed, Iremember I observed they talked of the King of Sweden as a prince ofno consideration, one that they might let go on and tire himself inMecklenburg and thereabout, till they could find leisure to deal withhim, and then might be crushed as they pleased; but 'tis never safeto despise an enemy, so this was not an enemy to be despised, as theyafterwards found.

As to the Conclusions of Leipsic, indeed, at first they gave theImperial court some uneasiness, but when they found the Imperialarmies, began to fright the members out of the union, and that theseveral branches had no considerable forces on foot, it was thegeneral discourse at Vienna, that the union at Leipsic only gavethe emperor an opportunity to crush absolutely the Dukes of Saxony,Brandenburg, and the Landgrave of Hesse, and they looked upon it as athing certain.

I never saw any real concern in their faces at Vienna till news cameto court that the King of Sweden had entered into the union; but asthis made them very uneasy, they began to move the powerfulest methodspossible to divert this storm; and upon this news Tilly was hastenedto fall into Saxony before this union could proceed to a conjunctionof forces. This was certainly a very good resolution, and no measurecould have been more exactly concerted, had not the diligence of theSaxons prevented it.

The gathering of this storm, which from a cloud began to spread overthe empire, and from the little duchy of Mecklenburg began to threatenall Germany, absolutely determined me, as I noted before, as totravelling, and laying aside the thoughts of Hungary, I resolved, ifpossible, to see the King of Sweden's army.

I parted from Vienna the middle of May, and took post for Great Glogauin Silesia, as if I had purposed to pass into Poland, but designingindeed to go down the Oder to Custrim in the marquisate ofBrandenburg, and so to Berlin. But when I came to the frontiers ofSilesia, though I had passes, I could go no farther, the guards onall the frontiers were so strict, so I was obliged to come back intoBohemia, and went to Prague. From hence I found I could easily passthrough the Imperial provinces to the lower Saxony, and accordinglytook passes for Hamburg, designing, however, to use them no fartherthan I found occasion.

By virtue of these passes I got into the Imperial army, under CountTilly, then at the siege of Magdeburg, May the 2nd.

I confess I did not foresee the fate of this city, neither, I believe,did Count Tilly himself expect to glut his fury with so entire adesolation, much less did the people expect it. I did believe theymust capitulate, and I perceived by discourse in the army that Tillywould give them but very indifferent conditions; but it fell outotherwise. The treaty of surrender was, as it were, begun, nay, somesay concluded, when some of the out-guards of the Imperialists findingthe citizens had abandoned the guards of the works, and looked tothemselves with less diligence than usual, they broke in, carried anhalf-moon, sword in hand, with little resistance; and though it wasa surprise on both sides, the ci

tizens neither fearing, nor the armyexpecting the occasion, the garrison, with as much resolution as couldbe expected under such a fright, flew to the walls, twice beat theImperialists off, but fresh men coming up, and the administrator ofMagdeburg himself being wounded and taken, the enemy broke in, tookthe city by storm, and entered with such terrible fury, that,without respect to age or condition, they put all the garrison andinhabitants, man, woman, and child, to the sword, plundered the city,and when they had done this set it on fire.

This calamity sure was the dreadfulest sight that ever I saw; therage of the Imperial soldiers was most intolerable, and not to beexpressed. Of 25,000, some said 30,000 people, there was not a soul tobe seen alive, till the flames drove those that were hid in vaults andsecret places to seek death in the streets rather than perish in thefire. Of these miserable creatures some were killed too by the furioussoldiers, but at last they saved the lives of such as came out oftheir cellars and holes, and so about two thousand poor desperatecreatures were left. The exact number of those that perished inthis city could never be known, because those the soldiers had firstbutchered the flames afterwards devoured.

I was on the outer side of the Elbe when this dreadful piece ofbutchery was done. The city of Magdeburg had a sconce or fort overagainst it called the toll-house, which joined to the city by a veryfine bridge of boats. This fort was taken by the Imperialists a fewdays before, and having a mind to see it, and the rather because fromthence I could have a very good view of the city, I was going overTilley's bridge of boats to view this fort. About ten o'clock in themorning I perceived they were storming by the firing, and immediatelyall ran to the works; I little thought of the taking the city, butimagined it might be some outwork attacked, for we all expectedthe city would surrender that day, or next, and they might havecapitulated upon very good terms.

Being upon the works of the fort, on a sudden I heard the dreadfulestcry raised in the city that can be imagined; 'tis not possible toexpress the manner of it, and I could see the women and childrenrunning about the streets in a most lamentable condition.

The city wall did not run along the side where the river was withso great a height, but we could plainly see the market-place and theseveral streets which run down to the river. In about an hour's timeafter this first cry all was in confusion; there was little shooting,the execution was all cutting of throats and mere house murders. Theresolute garrison, with the brave Baron Falkenberg, fought it outto the last, and were cut in pieces, and by this time the Imperialsoldiers having broke open the gates and entered on all sides, theslaughter was very dreadful. We could see the poor people in crowdsdriven down the streets, flying from the fury of the soldiers, whofollowed butchering them as fast as they could, and refused mercy toanybody, till driving them to the river's edge, the desperate wretcheswould throw themselves into the river, where thousands of themperished, especially women and children. Several men that could swimgot over to our side, where the soldiers not heated with fight gavethem quarter, and took them up, and I cannot but do this justice tothe German officers in the fort: they had five small flat boats, andthey gave leave to the soldiers to go off in them, and get what bootythey could, but charged them not to kill anybody, but take them allprisoners.

Nor was their humanity ill rewarded, for the soldiers, wisely avoidingthose places where their fellows were employed in butchering themiserable people, rowed to other places, where crowds of people stoodcrying out for help, and expecting to be every minute either drownedor murdered; of these at sundry times they fetched over near sixhundred, but took care to take in none but such as offered them goodpay.

Never was money or jewels of greater service than now, for those thathad anything of that sort to offer were soonest helped.

There was a burgher of the town who, seeing a boat coming near him,but out of his call, by the help of a speaking trumpet, told thesoldiers in it he would give them 20,000 dollars to fetch him off.They rowed close to the shore, and got him with his wife and sixchildren into the boat, but such throngs of people got about the boatthat had like to have sunk her, so that the soldiers were fain todrive a great many out again by main force, and while they were doingthis some of the enemies coming down the street desperately drove themall into the water.

The boat, however, brought the burgher and his wife and children safe,and though they had not all that wealth about them, yet in jewels andmoney he gave them so much as made all the fellows very rich.

I cannot pretend to describe the cruelty of this day: the town byfive in the afternoon was all in a flame; the wealth consumed wasinestimable, and a loss to the very conqueror. I think there waslittle or nothing left but the great church and about a hundredhouses.

This was a sad welcome into the army for me, and gave me a horror andaversion to the emperor's people, as well as to his cause. I quittedthe camp the third day after this execution, while the fire was hardlyout in the city; and from thence getting safe-conduct to pass into thePalatinate, I turned out of the road at a small village on the Elbe,called Emerfield, and by ways and towns I can give but small accountof, having a boor for our guide, whom we could hardly understand, Iarrived at Leipsic on the 17th of May.

We found the elector intense upon the strengthening of his army, butthe people in the greatest terror imaginable, every day expectingTilly with the German army, who by his cruelty at Magdeburg was becomeso dreadful to the Protestants that they expected no mercy wherever hecame.

The emperor's power was made so formidable to all the Protestants,particularly since the Diet at Ratisbon left them in a worse casethan it found them, that they had not only formed the Conclusions ofLeipsic, which all men looked on as the effect of desperation ratherthan any probable means of their deliverance, but had privatelyimplored the protection and assistance of foreign powers, andparticularly the King of Sweden, from whom they had promises of aspeedy and powerful assistance. And truly if the Swede had not witha very strong hand rescued them, all their Conclusions at Leipsic hadserved but to hasten their ruin. I remember very well when I was inthe Imperial army they discoursed with such contempt of the forcesof the Protestant, that not only the Imperialists but the Protestantsthemselves gave them up as lost. The emperor had not less than 200,000men in several armies on foot, who most of them were on the back ofthe Protestants in every corner. If Tilly did but write a threateningletter to any city or prince of the union, they presently submitted,renounced the Conclusions of Leipsic, and received Imperial garrisons,as the cities of Ulm and Memmingen, the duchy of Wirtemberg, andseveral others, and almost all Suaben.

Only the Duke of Saxony and the Landgrave of Hesse upheld the droopingcourage of the Protestants, and refused all terms of peace, slightedall the threatenings of the Imperial generals, and the Duke ofBrandenburg was brought in afterward almost by force.

The Duke of Saxony mustered his forces under the walls of Leipsic,and I having returned to Leipsic, two days before, saw them pass thereview. The duke, gallantly mounted, rode through the ranks, attendedby his field-marshal Arnheim, and seemed mighty well pleased withthem, and indeed the troops made a very fine appearance; but I thathad seen Tilly's army and his old weather-beaten soldiers, whosediscipline and exercises were so exact, and their courage so oftentried, could not look on the Saxon army without some concern for themwhen I considered who they had to deal with. Tilly's men were ruggedsurly fellows, their faces had an air of hardy courage, mangled withwounds and scars, their armour showed the bruises of musket bullets,and the rust of the winter storms. I observed of them their clotheswere always dirty, but their arms were clean and bright; they wereused to camp in the open fields, and sleep in the frosts and rain;their horses were strong and hardy like themselves, and well taughttheir exercises; the soldiers knew their business so exactly thatgeneral orders were enough; every private man was fit to command, andtheir wheelings, marchings, counter-marchings and exercise were donewith such order and readiness, that the distinct words of commandwere hardly of any use among them; they were flushed with

victory, andhardly knew what it was to fly.

There had passed some messages between Tilly and the duke, and he gavealways such ambiguous answers as he thought might serve to gain time;but Tilly was not to be put off with words, and drawing his armytowards Saxony, sends four propositions to him to sign, and demands animmediate reply. The propositions were positive.

1. To cause his troops to enter into the emperor's service, and tomarch in person with them against the King of Sweden.

2. To give the Imperial army quarters in his country, and supply themwith necessary provisions.

3. To relinquish the union of Leipsic, and disown the ten Conclusions.

4. To make restitution of the goods and lands of the Church.

The duke being pressed by Tilly's trumpeter for an immediate answersat all night, and part of the next day, in council with his privycouncillors, debating what reply to give him, which at last wasconcluded, in short, that he would live and die in defence of theProtestant religion, and the Conclusions of Leipsic, and bade Tillydefiance.