- Home

- Daniel Defoe

Robinson Crusoe (Penguin ed.) Page 2

Robinson Crusoe (Penguin ed.) Read online

Page 2

When his patron Harley (and the Tory government) fell from power in 1714 with the death of Queen Anne and the accession of George I, the German Elector of Hanover, Defoe had to scramble to survive and to find new patrons for his work as a writer. It is now known that he went to work for the new Whig government as a covert moderating influence through his political journalism on extreme Tory opinion. At the behest of the ministry, he edited the Tory monthly journal Mercurius Politicus from 1716 to 1720. He also in 1717 infiltrated the rabidly Tory Mist’s Weekly Journal, although his voice was soon recognized and he was attacked by Whig pamphleteers. In later years he continued this secret undermining of the opposition in his work for other papers. What makes all this journalistic work of interest for the modern student of Defoe and especially for readers of his fictional narratives is his extraordinary capacity for disguise and impersonation, his facility for projecting himself into the personalities and ideas of other people, to ventriloquize or mimic so effectively the voices of other people.

It is perhaps no accident that the political journalist and secret agent, the government’s mole in the opposition press, turned in 1719 to writing fiction, since for most of his life he had been playing roles and assuming identities distinct from his own. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, followed a few months later by its sequel, The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, is the beginning of a remarkable series of fictionalized autobiographical narratives that we nowadays call novels: Memoirs of a Cavalier, Captain Singleton (1720); Moll Flanders, A Journal of the Plague Year, Colonel Jack (1722); and Roxana (1724). But even as he was churning out these fictions, he continued to write prolifically in other formats and genres. The list of just some of his books during these last twelve years of his life is varied and extensive: Religious Courtship (1722), A New Voyage Round the World (1724), A Tour thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain (3 volumes, 1724–6), The Complete English Tradesman (2 volumes, 1725–7), The Political History of the Devil (1726), Conjugal Lewdness; or Matrimonial Whoredom. A Treatise concerning the Use and Abuse of the Marriage Bed (1727), An Essay on the History and Reality of Apparitions (1727), A Plan of the English Commerce (1728) and The Compleat English Gentleman (written 1729).

Like these multifarious productions – conduct books, moral polemics, travel narratives, popular economic and theological treatises, collections of ghost stories – Robinson Crusoe is first and foremost a response to commercial possibilities and opportunities in the early-eighteenth-century publishing market, Defoe’s effort to give the public what he thought they would buy. Capitalizing on its instant popularity, Defoe produced a sequel in that same year, in which Crusoe not only returns to his island but travels to the Far East, to China, and overland through Asia to Russia and then home to England. The subtitle of the first part appeals breathlessly to an audience envisioned as hungry for narratives of travel to exotic places, for sensational and unusual adventures and breathtaking wonder and mystery.

The germ for the book seems to have come from the experiences of an actual marooned sailor, the Scotsman Alexander Selkirk (1676–1721), who was part of a privateering expedition of several ships led by William Dampier to prey on Spanish merchant ships. In 1704, Selkirk quarrelled with his captain, Thomas Stradling, and asked to be set ashore on one of the small islands of the Juan Fernandez group some three hundred and fifty miles off the coast of Chile in the Pacific. (This island, Mas à Tierra, is now officially called Isla Robinson Crusoe, even though Defoe placed Crusoe’s island thousands of miles to the north in the Caribbean!) Four and a half years later, Selkirk was picked up by an English ship under the command of Captain Woodes Rogers, who had been part of the expedition that dropped Selkirk on the island. When Selkirk returned to England in 1711, he achieved a certain fame when Richard Steele wrote about him in 1713–14 in his periodical The Englishman. Defoe himself may also have met Selkirk, but the sailor’s story provided only the bare starting point. Selkirk’s tale is a tabloid headline – SAILOR SURVIVES FOUR YEARS ON DESERTED ISLAND!, a curious anecdote of a sojourn in which, as Steele reports it, the sailor reverted to a kind of natural state, living naked as his clothes wore out, learning to do without bread and salt for his meat, catching goats by running after them on bare feet, which grew hardened with use. In the interview with Steele, Selkirk remembered his days on the island as idyllic: ‘This manner of Life grew so exquisitely pleasant, that he never had a Moment heavy upon his Hands; his Nights were untroubled, and his Days joyous, from the Practice of Temperance and Exercise. It was his Manner to use stated Hours and Places for Exercises of Devotion, which he performed aloud, in order to keep up the Faculties of Speech, and to utter himself with greater Energy.’1 So Selkirk’s story celebrates the virtues of isolation: regression to a primitive or natural state accompanied by sentimental, unwordly contentment in delicious solitude. He tells Steele that he ‘frequently bewailed his Return to the World, which could not, he said, with all its Enjoyments, restore him to the Tranquility of his Solitude’.2 Defoe’s narrative largely avoids those sentimental popular themes and delivers instead a detailed account of the narrator’s physical survival on the island that includes a complex rendition of his psychological and religious development in an alienating, a distinctly dangerous solitude.

Literary historians have singled out Robinson Crusoe as perhaps the first true instance in English of what we now call the realistic novel. They mean that Defoe’s book fairly consistently renders its main character and narrator as a particularized individual situated in very recent history and society in all their moral and ideological complexity. Crusoe is not simply as the title declares a ‘mariner’. Thanks to the fullness and the acute particularity of the narrator and the world he evokes, Robinson is an individualized personality, an individual and not simply a type. Defoe implicitly subordinates the various moral and religious themes the book also explores to the rendering of that person in all his uniqueness and singularity. In place of Selkirk’s pastoral (and clichéd) contentment, Defoe dramatizes his hero’s deep ambivalence about his life and identity, his confusion, loneliness, sheer terror, self-loathing as well as growing self-knowledge and religious awareness gained through introspection that leads to confidence and to a powerful stewardship of the island and, finally, to successful mastering of the dangers that develop with the arrival of the cannibals and later of English mutineers. Crusoe’s narrative in the long run offers what the novel since Defoe’s time especially aspires to represent: personal growth, self-realization, development and maturation, as Robinson in his isolation overcomes his moral and physical limitations, finds solace and serenity in religious belief and material self-sufficiency and becomes master of himself as well as the lord of his island.

To be sure, for many twenty-first-century readers, Defoe’s book anticipates rather than fulfils the modern realistic novel to which they are accustomed. Psychologically and ideologically, Crusoe necessarily belongs to his time and place rather than ours, and not everyone will find Crusoe’s struggles with his faith in God’s Providence compelling or even convincing. The immediacy that Defoe was after in Crusoe’s ‘Journal’ doesn’t really work. The journal is an awkward narrative device that ends abruptly when he runs out of ink, and the net effect of inserting that day-to-day account into the retrospective narrative is at first distracting and then insignificant. After a while, some readers will be just a bit bored by Crusoe’s minute, wordy recording of his domestic arrangements on the island. Indeed, Defoe may have realized that the story of Crusoe’s survival tends to drag, so he introduces some excitement with the arrival of the cannibals and the mutineers and turns the book into an adventure story and away from a psycho-religious drama of survival.

The crucial narrative feature of Robinson Crusoe that makes it much more than a thrilling adventure story, however, is the narrator’s retrospective, intensely thoughtful perspective on his life. Robinson looks back from a wiser late middle age to his heedless and restles

s youthful days in which he disregarded his old father’s advice to stay at home instead of going to sea. Crusoe’s father counsels middle-class safety and comfort for his son as he evokes upper-class moral decadence and working-class (‘the mechanick part of mankind’) misery, but of course if we are to have a novel to read his son must disregard such sober advice, and these opening scenes of Crusoe’s rebellion establish him in a paradoxical position that will be maintained in various senses throughout. Looking back on his life, Crusoe will evoke an ambitious and aggressive younger individual but will tell his story from the perspective of a wiser and more mature man who has learned about the limitations on individual action and ambition and who has acquired the proper sense of divine or providential arrangement in human affairs. Crusoe’s divided personality returns us to the young Defoe, the pious Dissenter who wrestled with a call to the ministry but turned to the wheeling-and-dealing life of a businessman and entrepreneur in the emerging, rough and tumble proto-capitalist order of late-seventeenth-century England and Europe. On the one hand, Robinson Crusoe exemplifies the modern adventure capitalist, full of energy and resourceful ingenuity: his early years as a youthful trader to Africa (as well as a slave in Morocco) and a planter in Brazil show his determination and undaunted spirit. Crusoe is a young man ready to seek profit in the face of great risks and to manage his daring escape from slavery. On the other hand, Crusoe awakens to terror and existential confusion on his deserted island, alone and fearful of dangers all the more terrifying because they are unknown and uncertain. He avoids madness in this isolation by discovering God, by learning to read the Bible attentively and to find in his plight some signs of divine purpose and plan. Active and aggressive, independent and self-constructing, Robinson is also in time defined by his patient submission to God’s will, by his pious acceptance of a mysterious fate he can’t alter.

But Defoe also achieves a unique sense of another order of reality that contains the moral, social and theological realms in which Crusoe’s personal drama unfolds. Realism derives from the Latin word res (thing, object, matter), and Robinson Crusoe is a pioneering work of modern novelistic realism because Defoe renders for much of the narrative the force and feel of Crusoe’s material and phenomenal world with an unprecedented density and fine-grained immediacy and intricacy. Although Crusoe’s narrative is necessarily much concerned with his own thoughts and feelings, Defoe manages things so that his hero, especially on the island, situates those inner subjective explorations in a precisely and often minutely observed external objective world. Looking back, Crusoe shows us how he instinctively cooperated with the sequences of natural phenomena, their movements and rhythms, and thus survived the shipwreck and the solitude. That relationship anticipates his larger strategy on the island where he learns to cooperate with the nature of things, accommodating himself to the form and feel of the natural world that he needs to cultivate and manage for his survival.

To some extent, however, that natural world resists such management, and in a larger philosophical sense opposes human ordering. For the single most moving example of this tension between the exactly observed world Crusoe renders and his own ordering and understanding, consider the following moment just after Crusoe’s shipwreck:

I walk’d about on the shore, lifting up my hands, and my whole being, as I may say, wrapt up in the contemplation of my deliverance, making a thousand gestures and motions which I cannot describe, reflecting upon all my comrades that were drown’d, and that there should not be one soul sav’d but my self; for, as for them, I never saw them afterwards, or any sign of them, except three of their hats, one cap, and two shoes that were not fellows. (pp. 38–9)

‘Deliverance’ is a resonant moral-religious term that Crusoe will come to meditate upon during his early years on the island and learn to understand in a specific theological sense: he is delivered not simply from death but from spiritual indifference and ignorance of the workings of God’s Providence. But notice how this psychological moment – Crusoe’s longing for company and puzzlement over his singular fate – is inserted by the last almost casual but precise enumeration of objects in a faithfully observed world of absolutely random material happening where things manifest themselves without regard for order or human significance. That flotsam is endowed with tremendous pathos by Crusoe’s lonely plight. In their irreducible and impenetrable randomness, their tenuous connections to the people who once wore them, those hats, the cap and those two shoes that don’t match evoke a material world that is frighteningly arbitrary, impervious and indifferent to human emotions and ordering. These miscellaneous adjuncts of his dead comrades provide a bleak answer to Crusoe’s reflections about his survival: there is no meaning in events, just accident and chance, even in his singular fate. Like the single human footprint that Crusoe stumbles on later in the book, these objects and occurrences defy explanation and seem to exclude coherence or consolation. But for Crusoe they also provoke creative thought and transforming activity, and that is what makes him such a remarkable and resonant modern figure. In the midst of randomness and in the face of what looks like an arbitrary set of circumstances, he struggles and creates personal and satisfying order.

These are philosophical implications that Crusoe doesn’t dwell on at all, and this is not a language that he or Defoe would have understood. From his first few terrified days on the island (sleeping in a tree, fearful of wild animals and even more of unknown human enemies), Robinson moves on without hesitation to the tactics for survival. Resourceful, efficient and enterprising, he quickly gets busy and sets about stripping the wrecked ship of anything useful. The heart of the book and the centre of its longest episode is Crusoe painfully establishing himself on the island, exploiting the materials and tools (crucial technological supplements to his own intelligence and resourcefulness) that he salvages from the ship, building his cave and strengthening his fortifications, exploring his habitat and categorizing its useful as well as edible flora and fauna, charting its tides and its seasons, learning to hunt and to gather, to farm, to bake bread, to domesticate animals, to make pots and baskets and furniture and to fashion rough clothing (and, eventually, that most English of artifacts, an umbrella) for himself. All this activity has proved perennially fascinating to readers ever since, and Defoe’s novel has been most influential and imitated in this aspect. In edited and modernized versions, Robinson Crusoe is one of the most popular children’s books ever written. Crusoe building his fort and playing house, as it were, may be what children respond to with most delight, although the cannibals and mutineers who come later in the adventure are also part of the book’s perennial appeal.

Crusoe’s efficient outer life of rational application, mastering ‘mechanick’ arts and steadily producing goods, is balanced by the inner anxieties that provoke it; the outer calm and control balances deep and recurrent inner turmoil that Crusoe also charts for us. He spends a good deal of his time wondering obsessively and despairingly about the meaning of his situation, wondering ‘Why Providence should thus compleatly ruin its creatures, and render them so absolutely miserable, so without help abandon’d, so entirely depress’d, that it could hardly be rational to be thankful for such a life’ (p. 51). After an illness that leaves him weak and disoriented, after a terrifying dream that seems to be a signal from God, Crusoe records the following internal colloquy: ‘Why has God done this to me? What have I done to be thus us’d? My conscience presently check’d me in that enquiry, as if I had blasphem’d, and methought it spoke to me like a voice; WRETCH! dost thou ask what thou hast done! look back upon a dreadful mis-spent life, and ask thy self what thou hast not done? ask, Why is it that thou wert not long ago destroy’d?’ (pp. 74–5). His illness seems to be returning, so Crusoe takes up his Bible and finds in it at length words that seem to be meant for him and provoke an ecstatic conversion experience:

The impression of my dream reviv’d, and the words, All these things have not brought thee to repentance, ran seriously in my thought: I was earne

stly begging of God to give me repentance, when it happen’d providentially the very day that reading the Scripture, I came to these words, He is exalted a prince and a saviour, to give repentance, and to give remission: I threw down the book, and with my heart as well as my hands lifted up to Heaven, in a kind of extasy of joy, I cry’d out aloud, Jesus, thou son of David, Jesus, thou exalted prince and saviour, give me repentance! (p. 77)

One scholarly school of thought has identified Robinson Crusoe as rooted in Puritan spiritual autobiography, and such interpretations direct us to passages like this one as central to the book’s meanings. Puritans and other pious Protestants in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries were encouraged to keep religious diaries and to write spiritual autobiographies, accounts of how they came to feel that they were saved, records of their deepest feelings that were meant to assure themselves of God’s grace and to encourage them to keep their higher spiritual destinies in mind. Defoe’s novel, some of the time, fits this pattern, and Defoe himself can be said to have sanctioned this approach by publishing in 1720 Serious Reflections during the Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, a collection of essays and religious meditations presented as Crusoe’s religious reflections on the meaning of his story. He awakens from religious and spiritual indifference to a sense of God’s providential hand in his life. As complex and particularized as the events of his life are, they are shaped eventually in his mind by the master narrative of Christian salvation. In J. Paul Hunter’s phrase, Crusoe is a ‘reluctant pilgrim’; for Defoe and his eighteenth-century audience what looks like realistic detail to us has metaphorical overtones and emblematic as well as particular significance whereby Crusoe’s story primarily illustrates, as the preface puts it, ‘a religious application of events to the uses to which wise men always apply them (viz.) to the instruction of others by this example, and to justify and honour the wisdom of Providence in all the variety of our circumstances, let them happen how they will’ (p. 5).3

Captain Singleton

Captain Singleton An Essay Upon Projects

An Essay Upon Projects Moll Flanders Moll Flanders Moll Flanders

Moll Flanders Moll Flanders Moll Flanders The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Everybody's Business Is Nobody's Business

Everybody's Business Is Nobody's Business Robinson Crusoe

Robinson Crusoe The Storm

The Storm The King of Pirates

The King of Pirates History of the Plague in London

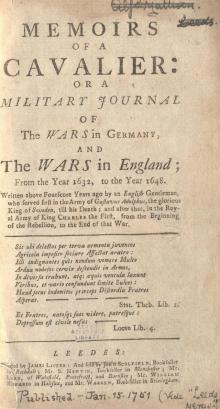

History of the Plague in London Memoirs of a Cavalier

Memoirs of a Cavalier_preview.jpg) The Life and Most Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner (1801)

The Life and Most Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner (1801) A Journal of the Plague Year

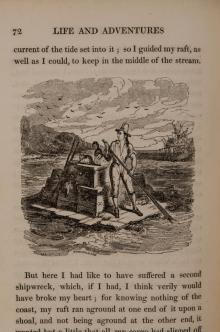

A Journal of the Plague Year_preview.jpg) The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1808)

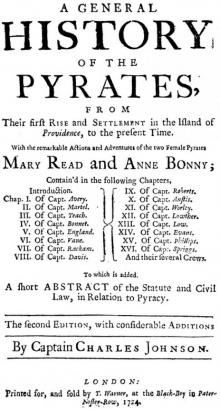

The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1808) A General History of the Pyrates: / from their first rise and settlement in the island of Providence, to the present time

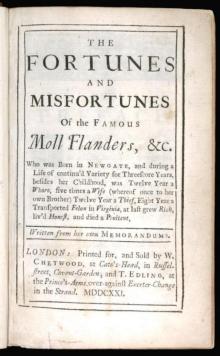

A General History of the Pyrates: / from their first rise and settlement in the island of Providence, to the present time The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders

The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders_preview.jpg) The Fortunate Mistress (Parts 1 and 2)

The Fortunate Mistress (Parts 1 and 2) Robinson Crusoe — in Words of One Syllable

Robinson Crusoe — in Words of One Syllable From London to Land's End

From London to Land's End A New Voyage Round the World by a Course Never Sailed Before

A New Voyage Round the World by a Course Never Sailed Before Roxana

Roxana The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, Volume 1

The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, Volume 1_preview.jpg) Memoirs of Major Alexander Ramkins (1718)

Memoirs of Major Alexander Ramkins (1718) Dickory Cronke

Dickory Cronke Robinson Crusoe (Penguin ed.)

Robinson Crusoe (Penguin ed.) Moll Flanders

Moll Flanders The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe rc-2

The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe rc-2