- Home

- Daniel Defoe

The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Page 2

The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Read online

Page 2

friend the widow, who earnestly struggled with me to consider my

years, my easy circumstances, and the needless hazards of a long

voyage; and above all, my young children. But it was all to no

purpose, I had an irresistible desire for the voyage; and I told

her I thought there was something so uncommon in the impressions I

had upon my mind, that it would be a kind of resisting Providence

if I should attempt to stay at home; after which she ceased her

expostulations, and joined with me, not only in making provision

for my voyage, but also in settling my family affairs for my

absence, and providing for the education of my children. In order

to do this, I made my will, and settled the estate I had in such a

manner for my children, and placed in such hands, that I was

perfectly easy and satisfied they would have justice done them,

whatever might befall me; and for their education, I left it wholly

to the widow, with a sufficient maintenance to herself for her

care: all which she richly deserved; for no mother could have

taken more care in their education, or understood it better; and as

she lived till I came home, I also lived to thank her for it.

My nephew was ready to sail about the beginning of January 1694-5;

and I, with my man Friday, went on board, in the Downs, the 8th;

having, besides that sloop which I mentioned above, a very

considerable cargo of all kinds of necessary things for my colony,

which, if I did not find in good condition, I resolved to leave so.

First, I carried with me some servants whom I purposed to place

there as inhabitants, or at least to set on work there upon my

account while I stayed, and either to leave them there or carry

them forward, as they should appear willing; particularly, I

carried two carpenters, a smith, and a very handy, ingenious

fellow, who was a cooper by trade, and was also a general mechanic;

for he was dexterous at making wheels and hand-mills to grind corn,

was a good turner and a good pot-maker; he also made anything that

was proper to make of earth or of wood: in a word, we called him

our Jack-of-all-trades. With these I carried a tailor, who had

offered himself to go a passenger to the East Indies with my

nephew, but afterwards consented to stay on our new plantation, and

who proved a most necessary handy fellow as could be desired in

many other businesses besides that of his trade; for, as I observed

formerly, necessity arms us for all employments.

My cargo, as near as I can recollect, for I have not kept account

of the particulars, consisted of a sufficient quantity of linen,

and some English thin stuffs, for clothing the Spaniards that I

expected to find there; and enough of them, as by my calculation

might comfortably supply them for seven years; if I remember right,

the materials I carried for clothing them, with gloves, hats,

shoes, stockings, and all such things as they could want for

wearing, amounted to about two hundred pounds, including some beds,

bedding, and household stuff, particularly kitchen utensils, with

pots, kettles, pewter, brass, &c.; and near a hundred pounds more

in ironwork, nails, tools of every kind, staples, hooks, hinges,

and every necessary thing I could think of.

I carried also a hundred spare arms, muskets, and fusees; besides

some pistols, a considerable quantity of shot of all sizes, three

or four tons of lead, and two pieces of brass cannon; and, because

I knew not what time and what extremities I was providing for, I

carried a hundred barrels of powder, besides swords, cutlasses, and

the iron part of some pikes and halberds. In short, we had a large

magazine of all sorts of store; and I made my nephew carry two

small quarter-deck guns more than he wanted for his ship, to leave

behind if there was occasion; so that when we came there we might

build a fort and man it against all sorts of enemies. Indeed, I at

first thought there would be need enough for all, and much more, if

we hoped to maintain our possession of the island, as shall be seen

in the course of that story.

I had not such bad luck in this voyage as I had been used to meet

with, and therefore shall have the less occasion to interrupt the

reader, who perhaps may be impatient to hear how matters went with

my colony; yet some odd accidents, cross winds and bad weather

happened on this first setting out, which made the voyage longer

than I expected it at first; and I, who had never made but one

voyage, my first voyage to Guinea, in which I might be said to come

back again, as the voyage was at first designed, began to think the

same ill fate attended me, and that I was born to be never

contented with being on shore, and yet to be always unfortunate at

sea. Contrary winds first put us to the northward, and we were

obliged to put in at Galway, in Ireland, where we lay wind-bound

two-and-twenty days; but we had this satisfaction with the

disaster, that provisions were here exceeding cheap, and in the

utmost plenty; so that while we lay here we never touched the

ship's stores, but rather added to them. Here, also, I took in

several live hogs, and two cows with their calves, which I

resolved, if I had a good passage, to put on shore in my island;

but we found occasion to dispose otherwise of them.

We set out on the 5th of February from Ireland, and had a very fair

gale of wind for some days. As I remember, it might be about the

20th of February in the evening late, when the mate, having the

watch, came into the round-house and told us he saw a flash of

fire, and heard a gun fired; and while he was telling us of it, a

boy came in and told us the boatswain heard another. This made us

all run out upon the quarter-deck, where for a while we heard

nothing; but in a few minutes we saw a very great light, and found

that there was some very terrible fire at a distance; immediately

we had recourse to our reckonings, in which we all agreed that

there could be no land that way in which the fire showed itself,

no, not for five hundred leagues, for it appeared at WNW. Upon

this, we concluded it must be some ship on fire at sea; and as, by

our hearing the noise of guns just before, we concluded that it

could not be far off, we stood directly towards it, and were

presently satisfied we should discover it, because the further we

sailed, the greater the light appeared; though, the weather being

hazy, we could not perceive anything but the light for a while. In

about half-an-hour's sailing, the wind being fair for us, though

not much of it, and the weather clearing up a little, we could

plainly discern that it was a great ship on fire in the middle of

the sea.

I was most sensibly touched with this disaster, though not at all

acquainted with the persons engaged in it; I presently recollected

my former circumstances, and what condition I was in when taken up

by the Portuguese captain; and how much more deplorable the

circumstances of the poor creatures belonging to that ship must be,

if they had no other ship in company with them. Upon this I

immediately ordered that five guns should be fired, one soon after

another, that, if possible, we might give notice to them that there

was help for them at hand and that they might endeavour to save

themselves in their boat; for though we could see the flames of the

ship, yet they, it being night, could see nothing of us.

We lay by some time upon this, only driving as the burning ship

drove, waiting for daylight; when, on a sudden, to our great

terror, though we had reason to expect it, the ship blew up in the

air; and in a few minutes all the fire was out, that is to say, the

rest of the ship sunk. This was a terrible, and indeed an

afflicting sight, for the sake of the poor men, who, I concluded,

must be either all destroyed in the ship, or be in the utmost

distress in their boat, in the middle of the ocean; which, at

present, as it was dark, I could not see. However, to direct them

as well as I could, I caused lights to be hung out in all parts of

the ship where we could, and which we had lanterns for, and kept

firing guns all the night long, letting them know by this that

there was a ship not far off.

About eight o'clock in the morning we discovered the ship's boats

by the help of our perspective glasses, and found there were two of

them, both thronged with people, and deep in the water. We

perceived they rowed, the wind being against them; that they saw

our ship, and did their utmost to make us see them. We immediately

spread our ancient, to let them know we saw them, and hung a waft

out, as a signal for them to come on board, and then made more

sail, standing directly to them. In little more than half-an-hour

we came up with them; and took them all in, being no less than

sixty-four men, women, and children; for there were a great many

passengers.

Upon inquiry we found it was a French merchant ship of three-

hundred tons, home-bound from Quebec. The master gave us a long

account of the distress of his ship; how the fire began in the

steerage by the negligence of the steersman, which, on his crying

out for help, was, as everybody thought, entirely put out; but they

soon found that some sparks of the first fire had got into some

part of the ship so difficult to come at that they could not

effectually quench it; and afterwards getting in between the

timbers, and within the ceiling of the ship, it proceeded into the

hold, and mastered all the skill and all the application they were

able to exert.

They had no more to do then but to get into their boats, which, to

their great comfort, were pretty large; being their long-boat, and

a great shallop, besides a small skiff, which was of no great

service to them, other than to get some fresh water and provisions

into her, after they had secured their lives from the fire. They

had, indeed, small hopes of their lives by getting into these boats

at that distance from any land; only, as they said, that they thus

escaped from the fire, and there was a possibility that some ship

might happen to be at sea, and might take them in. They had sails,

oars, and a compass; and had as much provision and water as, with

sparing it so as to be next door to starving, might support them

about twelve days, in which, if they had no bad weather and no

contrary winds, the captain said he hoped he might get to the banks

of Newfoundland, and might perhaps take some fish, to sustain them

till they might go on shore. But there were so many chances

against them in all these cases, such as storms, to overset and

founder them; rains and cold, to benumb and perish their limbs;

contrary winds, to keep them out and starve them; that it must have

been next to miraculous if they had escaped.

In the midst of their consternation, every one being hopeless and

ready to despair, the captain, with tears in his eyes, told me they

were on a sudden surprised with the joy of hearing a gun fire, and

after that four more: these were the five guns which I caused to

be fired at first seeing the light. This revived their hearts, and

gave them the notice, which, as above, I desired it should, that

there was a ship at hand for their help. It was upon the hearing

of these guns that they took down their masts and sails: the sound

coming from the windward, they resolved to lie by till morning.

Some time after this, hearing no more guns, they fired three

muskets, one a considerable while after another; but these, the

wind being contrary, we never heard. Some time after that again

they were still more agreeably surprised with seeing our lights,

and hearing the guns, which, as I have said, I caused to be fired

all the rest of the night. This set them to work with their oars,

to keep their boats ahead, at least that we might the sooner come

up with them; and at last, to their inexpressible joy, they found

we saw them.

It is impossible for me to express the several gestures, the

strange ecstasies, the variety of postures which these poor

delivered people ran into, to express the joy of their souls at so

unexpected a deliverance. Grief and fear are easily described:

sighs, tears, groans, and a very few motions of the head and hands,

make up the sum of its variety; but an excess of joy, a surprise of

joy, has a thousand extravagances in it. There were some in tears;

some raging and tearing themselves, as if they had been in the

greatest agonies of sorrow; some stark raving and downright

lunatic; some ran about the ship stamping with their feet, others

wringing their hands; some were dancing, some singing, some

laughing, more crying, many quite dumb, not able to speak a word;

others sick and vomiting; several swooning and ready to faint; and

a few were crossing themselves and giving God thanks.

I would not wrong them either; there might be many that were

thankful afterwards; but the passion was too strong for them at

first, and they were not able to master it: then were thrown into

ecstasies, and a kind of frenzy, and it was but a very few that

were composed and serious in their joy. Perhaps also, the case may

have some addition to it from the particular circumstance of that

nation they belonged to: I mean the French, whose temper is

allowed to be more volatile, more passionate, and more sprightly,

and their spirits more fluid than in other nations. I am not

philosopher enough to determine the cause; but nothing I had ever

seen before came up to it. The ecstasies poor Friday, my trusty

savage, was in when he found his father in the boat came the

nearest to it; and the surprise of the master and his two

companions, whom I delivered from the villains that set them on

shore in the island, came a little way towards it; but nothing was

to compare to this, either that I saw in Friday, or anywhere else

in my life.

It is further observable, that these extravagances did not show

themselves in that different ma

nner I have mentioned, in different

persons only; but all the variety would appear, in a short

succession of moments, in one and the same person. A man that we

saw this minute dumb, and, as it were, stupid and confounded, would

the next minute be dancing and hallooing like an antic; and the

next moment be tearing his hair, or pulling his clothes to pieces,

and stamping them under his feet like a madman; in a few moments

after that we would have him all in tears, then sick, swooning,

and, had not immediate help been had, he would in a few moments

have been dead. Thus it was, not with one or two, or ten or

twenty, but with the greatest part of them; and, if I remember

right, our surgeon was obliged to let blood of about thirty

persons.

There were two priests among them: one an old man, and the other a

young man; and that which was strangest was, the oldest man was the

worst. As soon as he set his foot on board our ship, and saw

himself safe, he dropped down stone dead to all appearance. Not

the least sign of life could be perceived in him; our surgeon

immediately applied proper remedies to recover him, and was the

only man in the ship that believed he was not dead. At length he

opened a vein in his arm, having first chafed and rubbed the part,

so as to warm it as much as possible. Upon this the blood, which

only dropped at first, flowing freely, in three minutes after the

man opened his eyes; a quarter of an hour after that he spoke, grew

better, and after the blood was stopped, he walked about, told us

he was perfectly well, and took a dram of cordial which the surgeon

gave him. About a quarter of an hour after this they came running

into the cabin to the surgeon, who was bleeding a Frenchwoman that

had fainted, and told him the priest was gone stark mad. It seems

he had begun to revolve the change of his circumstances in his

mind, and again this put him into an ecstasy of joy. His spirits

whirled about faster than the vessels could convey them, the blood

grew hot and feverish, and the man was as fit for Bedlam as any

creature that ever was in it. The surgeon would not bleed him

again in that condition, but gave him something to doze and put him

to sleep; which, after some time, operated upon him, and he awoke

next morning perfectly composed and well. The younger priest

behaved with great command of his passions, and was really an

example of a serious, well-governed mind. At his first coming on

board the ship he threw himself flat on his face, prostrating

himself in thankfulness for his deliverance, in which I unhappily

and unseasonably disturbed him, really thinking he had been in a

swoon; but he spoke calmly, thanked me, told me he was giving God

thanks for his deliverance, begged me to leave him a few moments,

and that, next to his Maker, he would give me thanks also. I was

heartily sorry that I disturbed him, and not only left him, but

kept others from interrupting him also. He continued in that

posture about three minutes, or little more, after I left him, then

came to me, as he had said he would, and with a great deal of

seriousness and affection, but with tears in his eyes, thanked me,

that had, under God, given him and so many miserable creatures

their lives. I told him I had no need to tell him to thank God for

it, rather than me, for I had seen that he had done that already;

but I added that it was nothing but what reason and humanity

dictated to all men, and that we had as much reason as he to give

thanks to God, who had blessed us so far as to make us the

instruments of His mercy to so many of His creatures. After this

the young priest applied himself to his countrymen, and laboured to

compose them: he persuaded, entreated, argued, reasoned with them,

and did his utmost to keep them within the exercise of their

reason; and with some he had success, though others were for a time

out of all government of themselves.

I cannot help committing this to writing, as perhaps it may be

useful to those into whose hands it may fall, for guiding

Captain Singleton

Captain Singleton An Essay Upon Projects

An Essay Upon Projects Moll Flanders Moll Flanders Moll Flanders

Moll Flanders Moll Flanders Moll Flanders The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Everybody's Business Is Nobody's Business

Everybody's Business Is Nobody's Business Robinson Crusoe

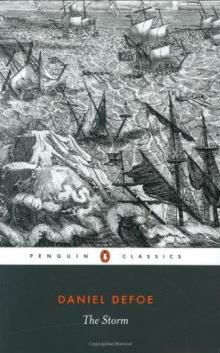

Robinson Crusoe The Storm

The Storm The King of Pirates

The King of Pirates History of the Plague in London

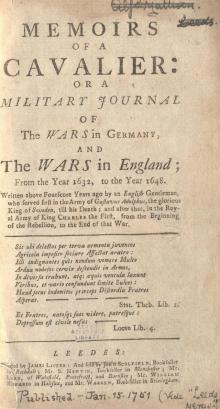

History of the Plague in London Memoirs of a Cavalier

Memoirs of a Cavalier_preview.jpg) The Life and Most Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner (1801)

The Life and Most Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner (1801) A Journal of the Plague Year

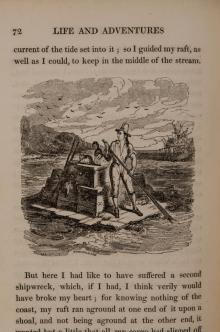

A Journal of the Plague Year_preview.jpg) The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1808)

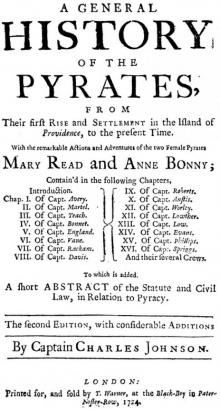

The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1808) A General History of the Pyrates: / from their first rise and settlement in the island of Providence, to the present time

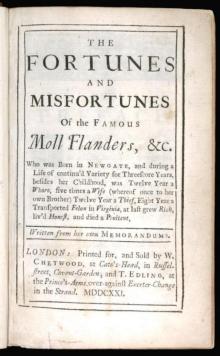

A General History of the Pyrates: / from their first rise and settlement in the island of Providence, to the present time The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders

The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders_preview.jpg) The Fortunate Mistress (Parts 1 and 2)

The Fortunate Mistress (Parts 1 and 2) Robinson Crusoe — in Words of One Syllable

Robinson Crusoe — in Words of One Syllable From London to Land's End

From London to Land's End A New Voyage Round the World by a Course Never Sailed Before

A New Voyage Round the World by a Course Never Sailed Before Roxana

Roxana The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, Volume 1

The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, Volume 1_preview.jpg) Memoirs of Major Alexander Ramkins (1718)

Memoirs of Major Alexander Ramkins (1718) Dickory Cronke

Dickory Cronke Robinson Crusoe (Penguin ed.)

Robinson Crusoe (Penguin ed.) Moll Flanders

Moll Flanders The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe rc-2

The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe rc-2