- Home

- Daniel Defoe

An Essay Upon Projects Page 2

An Essay Upon Projects Read online

Page 2

Dr. Annesley, and by his advice sent to the Academy at Newington

Green, where Charles Morton, a good Oxford scholar, trained young

men for the pulpits of the Nonconformists. In later days, when

driven to America by the persecution of opinion, Morton became Vice-

President of Harvard College. Charles Morton sought to include in

his teaching at Newington Green a training in such knowledge of

current history as would show his boys the origin and meaning of the

controversies of the day in which, as men, they might hereafter take

their part. He took pains, also, to train them in the use of

English. "We were not," Defoe said afterwards, "destitute of

language, but we were made masters of English; and more of us

excelled in that particular than of any school at that time."

Daniel Foe did not pass on into the ministry for which he had been

trained. He said afterwards, in his "Review," "It was my disaster

first to be set apart for, and then to be set apart from, the honour

of that sacred employ." At the age of about nineteen he went into

business as a hose factor in Freeman's Court, Cornhill. He may have

bought succession to a business, or sought to make one in a way of

life that required no capital. He acted simply as broker between

the manufacturer and the retailer. He remained at the business in

Freeman's Court for seven years, subject to political distractions.

In 1683, still in the reign of Charles the Second, Daniel Foe, aged

twenty-two, published a pamphlet called "Presbytery Roughdrawn."

Charles died on the 6th of February, 1685. On the 14th of the next

June the Duke of Monmouth landed at Lyme with eighty-three

followers, hoping that Englishmen enough would flock about his

standard to overthrow the Government of James the Second, for whose

exclusion, as a Roman Catholic, from the succession to the throne

there had been so long a struggle in his brother's reign. Daniel

Foe took leave of absence from his business in Freeman's Court,

joined Monmouth, and shared the defeat at Sedgmoor on the 6th of

July. Judge Jeffreys then made progress through the West, and

Daniel Foe escaped from his clutches. On the 15th of July Monmouth

was executed. Daniel Foe found it convenient at that time to pay

personal attention to some business affairs in Spain. His name

suggests an English reading of a Spanish name, Foa, and more than

once in his life there are indications of friends in Spain about

whom we know nothing. Daniel Foe went to Spain in the time of

danger to his life, for taking part in the rebellion of the Duke of

Monmouth, and when he came back he wrote himself De Foe. He may

have heard pedigree discussed among his Spanish friends; he may have

wished to avoid drawing attention to a name entered under the letter

F in a list of rebels. He may have played on the distinction

between himself and his father, still living, that one was Mr. Foe,

the other Mr. D. Foe. He may have meant to write much, and wishing

to be a friend to his country, meant also to deprive punsters of the

opportunity of calling him a Foe. Whatever his chief reason for the

change, we may be sure that it was practical.

In April, 1687, James the Second issued a Declaration for Liberty of

Conscience in England, by which he suspended penal laws against all

Roman Catholics and Nonconformists, and dispensed with oaths and

tests established by the law. This was a stretch of the king's

prerogative that produced results immediately welcome to the

Nonconformists, who sent up addresses of thanks. Defoe saw clearly

that a king who is thanked for overruling an unwelcome law has the

whole point conceded to him of right to overrule the law. In that

sense he wrote, "A Letter containing some Reflections on His

Majesty's Declaration for Liberty of Conscience," to warn the

Nonconformists of the great mistake into which some were falling.

"Was ever anything," he asked afterwards, "more absurd than this

conduct of King James and his party, in wheedling the Dissenters;

giving them liberty of conscience by his own arbitrary dispensing

authority, and his expecting they should be content with their

religious liberty at the price of the Constitution?" In the letter

itself he pointed out that "the king's suspending of laws strikes at

the root of this whole Government, and subverts it quite. The Lords

and Commons have such a share in it, that no law can be either made,

repealed, or, which is all one, suspended, but by their consent."

In January, 1688, Defoe having inherited the freedom of the City of

London, took it up, and signed his name in the Chamberlain's book,

on the 26th of that month, without the "de," "Daniel Foe." On the

5th of November, 1688, there was another landing, that of William of

Orange, in Torbay, which threatened the government of James the

Second. Defoe again rode out, met the army of William at Henley-on-

Thames, and joined its second line as a volunteer. He was present

when it was resolved, on the 13th of February, 1689, that the flight

of James had been an abdication; and he was one of the mounted

citizens who formed a guard of honour when William and Mary paid

their first visit to Guildhall.

Defoe was at this time twenty-eight years old, married, and living

in a house at Tooting, where he had also been active in foundation

of a chapel. From hose factor he had become merchant adventurer in

trade with Spain, and is said by one writer of his time to have been

a "civet-cat merchant." Failing then in some venture in 1692, he

became bankrupt, and had one vindictive creditor who, according to

the law of those days, had power to shut him in prison, and destroy

all power of recovering his loss and putting himself straight with

the world. Until his other creditors had conquered that one enemy,

and could give him freedom to earn money again and pay his debts--

when that time came he proved his sense of honesty to much larger

than the letter of the law--Defoe left London for Bristol, and there

kept out of the way of arrest. He was visible only on Sunday, and

known, therefore, as "the Sunday Gentleman." His lodging was at the

Red Lion Inn, in Castle Street. The house, no longer an inn, still

stands, as numbers 80 and 81 in that street. There Defoe wrote this

Essay on Projects." He was there until 1694, when he received

offers that would have settled him prosperously in business at

Cadiz, but he held by his country. The cheek on free action was

removed, and the Government received with favour a project of his,

which is not included in the Essay, "for raising money to supply the

occasions of the war then newly begun." He had also a project for

the raising of money to supply his own occasions by the

establishment of pantile works, which proved successful. Defoe

could not be idle. In a desert island he would, like his Robinson

Crusoe, have spent time, not in lamentation, but in steady work to

get away.

H. M.

AUTHOR'S PREFACE.

TO DALBY THOMAS,

ESQ., One of the Commission's for Managing His

majesty's Duties on Glass, &c

SIR,

This Preface comes directed to you, not as commissioner, &c., under

whom I have the honour to serve his Majesty, nor as a friend, though

I have great obligations of that sort also, but as the most proper

judge of the subjects treated of, and more capable than the greatest

part of mankind to distinguish and understand them.

Books are useful only to such whose genius are suitable to the

subject of them; and to dedicate a book of projects to a person who

had never concerned himself to think that way would be like music to

one that has no ear.

And yet your having a capacity to judge of these things no way

brings you under the despicable title of a projector, any more than

knowing the practices and subtleties of wicked men makes a man

guilty of their crimes.

The several chapters of this book are the results of particular

thoughts occasioned by conversing with the public affairs during the

present war with France. The losses and casualties which attend all

trading nations in the world, when involved in so cruel a war as

this, have reached us all, and I am none of the least sufferers; if

this has put me, as well as others, on inventions and projects, so

much the subject of this book, it is no more than a proof of the

reason I give for the general projecting humour of the nation.

One unhappiness I lie under in the following book, viz.: That

having kept the greatest part of it by me for near five years,

several of the thoughts seem to be hit by other hands, and some by

the public, which turns the tables upon me, as if I had borrowed

from them.

As particularly that of the seamen, which you know well I had

contrived long before the Act for registering seamen was proposed.

And that of educating women, which I think myself bound to declare,

was formed long before the book called "Advice to the Ladies" was

made public; and yet I do not write this to magnify my own

invention, but to acquit myself from grafting on other people's

thoughts. If I have trespassed upon any person in the world, it is

upon yourself, from whom I had some of the notions about county

banks, and factories for goods, in the chapter of banks; and yet I

do not think that my proposal for the women or the seamen clashes at

all, either with that book, or the public method of registering

seamen.

I have been told since this was done that my proposal for a

commission of inquiries into bankrupt estates is borrowed from the

Dutch; if there is anything like it among the Dutch, it is more than

ever I knew, or know yet; but if so, I hope it is no objection

against our having the same here, especially if it be true that it

would be so publicly beneficial as is expressed.

What is said of friendly societies, I think no man will dispute with

me, since one has met with so much success already in the practice

of it. I mean the Friendly Society for Widows, of which you have

been pleased to be a governor.

Friendly societies are very extensive, and, as I have hinted, might

be carried on to many particulars. I have omitted one which was

mentioned in discourse with yourself, where a hundred tradesmen, all

of several trades, agree together to buy whatever they want of one

another, and nowhere else, prices and payments to be settled among

themselves; whereby every man is sure to have ninety-nine customers,

and can never want a trade; and I could have filled up the book with

instances of like nature, but I never designed to fire the reader

with particulars.

The proposal of the pension office you will soon see offered to the

public as an attempt for the relief of the poor; which, if it meets

with encouragement, will every way answer all the great things I

have said of it.

I had wrote a great many sheets about the coin, about bringing in

plate to the Mint, and about our standard; but so many great heads

being upon it, with some of whom my opinion does not agree, I would

not adventure to appear in print upon that subject.

Ways and means also I have laid by on the same score: only adhering

to this one point, that be it by taxing the wares they sell, be it

by taxing them in stock, be it by composition--which, by the way, I

believe is the best--be it by what way soever the Parliament please,

the retailers are the men who seem to call upon us to be taxed; if

not by their own extraordinary good circumstances, though that might

bear it, yet by the contrary in all other degrees of the kingdom.

Besides, the retailers are the only men who could pay it with least

damage, because it is in their power to levy it again upon their

customers in the prices of their goods, and is no more than paying a

higher rent for their shops.

The retailers of manufactures, especially so far as relates to the

inland trade, have never been taxed yet, and their wealth or number

is not easily calculated. Trade and land has been handled roughly

enough, and these are the men who now lie as a reserve to carry on

the burden of the war.

These are the men who, were the land tax collected as it should be,

ought to pay the king more than that whole Bill ever produced; and

yet these are the men who, I think I may venture to say, do not pay

a twentieth part in that Bill.

Should the king appoint a survey over the assessors, and indict all

those who were found faulty, allowing a reward to any discoverer of

an assessment made lower than the literal sense of the Act implies,

what a register of frauds and connivances would be found out!

In a general tax, if any should be excused, it should be the poor,

who are not able to pay, or at least are pinched in the necessary

parts of life by paying. And yet here a poor labourer, who works

for twelve pence or eighteen pence a day, does not drink a pot of

beer but pays the king a tenth part for excise; and really pays more

to the king's taxes in a year than a country shopkeeper, who is

alderman of the town, worth perhaps two or three thousand pounds,

brews his own beer, pays no excise, and in the land-tax is rated it

may be at 100 pounds, and pays 1 pound 4s. per annum, but ought, if

the Act were put in due execution, to pay 36 pounds per annum to the

king.

If I were to be asked how I would remedy this, I would answer, it

should be by some method in which every man may be taxed in the due

proportion to his estate, and the Act put in execution, according to

the true intent and meaning of it, in order to which a commission of

assessment should be granted to twelve men, such as his Majesty

should be well satisfied of, who should go through the whole

kingdom, three in a body, and should make a new assessment of

personal estates, not to meddle with land.

To these assessors should all the old rates, parish books, poor

rates, and highway rates, also be delivered; and upon due inquiry to

be made into the manner of living, an

d reputed wealth of the people,

the stock or personal estate of every man should be assessed,

without connivance; and he who is reputed to be worth a thousand

pounds should be taxed at a thousand pounds, and so on; and he who

was an overgrown rich tradesman of twenty or thirty thousand pounds

estate should be taxed so, and plain English and plain dealing be

practised indifferently throughout the kingdom; tradesmen and landed

men should have neighbours' fare, as we call it, and a rich man

should not be passed by when a poor man pays.

We read of the inhabitants of Constantinople, that they suffered

their city to be lost for want of contributing in time for its

defence, and pleaded poverty to their generous emperor when he went

from house to house to persuade them; and yet when the Turks took

it, the prodigious immense wealth they found in it, made them wonder

at the sordid temper of the citizens.

England (with due exceptions to the Parliament, and the freedom

wherewith they have given to the public charge) is much like

Constantinople; we are involved in a dangerous, a chargeable, but

withal a most just and necessary war, and the richest and moneyed

men in the kingdom plead poverty; and the French, or King James, or

the devil may come for them, if they can but conceal their estates

from the public notice, and get the assessors to tax them at an

under rate.

These are the men this commission would discover; and here they

should find men taxed at 500 pounds stock who are worth 20,000

pounds. Here they should find a certain rich man near Hackney rated

to-day in the tax-book at 1,000 pounds stock, and to-morrow offering

27,000 pounds for an estate.

Here they should find Sir J- C- perhaps taxed to the king at 5,000

pounds stock, perhaps not so much, whose cash no man can guess at;

and multitudes of instances I could give by name without wrong to

the gentlemen.

And, not to run on in particulars, I affirm that in the land-tax ten

certain gentlemen in London put together did not pay for half so

much personal estate, called stock, as the poorest of them is

reputed really to possess.

I do not inquire at whose door this fraud must lie; it is none of my

business.

I wish they would search into it whose power can punish it. But

this, with submission, I presume to say: The king is thereby

defrauded and horribly abused, the true intent and meaning of Acts

of Parliament evaded, the nation involved in debt by fatal

deficiencies and interests, fellow-subjects abused, and new

inventions for taxes occasioned.

The last chapter in this book is a proposal about entering all the

seamen in England into the king's pay--a subject which deserves to

be enlarged into a book itself; and I have a little volume of

calculations and particulars by me on that head, but I thought them

too long to publish. In short, I am persuaded, was that method

proposed to those gentlemen to whom such things belong, the greatest

sum of money might be raised by it, with the least injury to those

who pay it, that ever was or will be during the war.

Projectors, they say, are generally to be taken with allowance of

one-half at least; they always have their mouths full of millions,

and talk big of their own proposals. And therefore I have not

exposed the vast sums my calculations amount to; but I venture to

say I could procure a farm on such a proposal as this at three

millions per annum, and give very good security for payment--such an

opinion I have of the value of such a method; and when that is done,

the nation would get three more by paying it, which is very strange,

but might easily be made out.

In the chapter of academies I have ventured to reprove the vicious

custom of swearing. I shall make no apology for the fact, for no

man ought to be ashamed of exposing what all men ought to be ashamed

of practising. But methinks I stand corrected by my own laws a

Captain Singleton

Captain Singleton An Essay Upon Projects

An Essay Upon Projects Moll Flanders Moll Flanders Moll Flanders

Moll Flanders Moll Flanders Moll Flanders The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Everybody's Business Is Nobody's Business

Everybody's Business Is Nobody's Business Robinson Crusoe

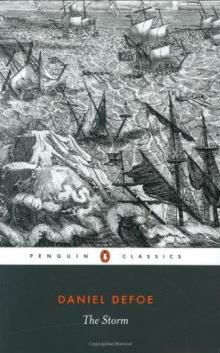

Robinson Crusoe The Storm

The Storm The King of Pirates

The King of Pirates History of the Plague in London

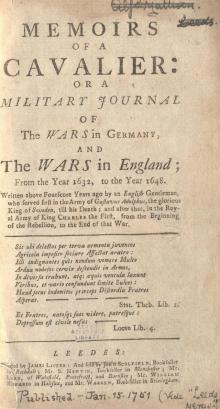

History of the Plague in London Memoirs of a Cavalier

Memoirs of a Cavalier_preview.jpg) The Life and Most Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner (1801)

The Life and Most Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner (1801) A Journal of the Plague Year

A Journal of the Plague Year_preview.jpg) The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1808)

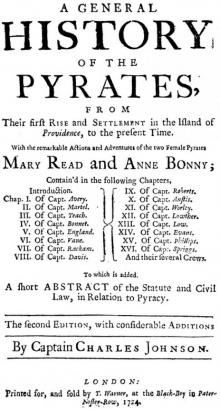

The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1808) A General History of the Pyrates: / from their first rise and settlement in the island of Providence, to the present time

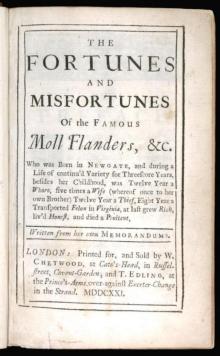

A General History of the Pyrates: / from their first rise and settlement in the island of Providence, to the present time The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders

The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders_preview.jpg) The Fortunate Mistress (Parts 1 and 2)

The Fortunate Mistress (Parts 1 and 2) Robinson Crusoe — in Words of One Syllable

Robinson Crusoe — in Words of One Syllable From London to Land's End

From London to Land's End A New Voyage Round the World by a Course Never Sailed Before

A New Voyage Round the World by a Course Never Sailed Before Roxana

Roxana The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, Volume 1

The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, Volume 1_preview.jpg) Memoirs of Major Alexander Ramkins (1718)

Memoirs of Major Alexander Ramkins (1718) Dickory Cronke

Dickory Cronke Robinson Crusoe (Penguin ed.)

Robinson Crusoe (Penguin ed.) Moll Flanders

Moll Flanders The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe rc-2

The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe rc-2