- Home

- Daniel Defoe

Moll Flanders Page 15

Moll Flanders Read online

Page 15

In a word, I avoided a contract, but told him I would go into the north; that he would know where to write to me by the business I had entrusted him with; that I would give him a sufficient pledge of my respect for him, for I would leave almost all I had in the world in his hands; and I would thus far give him my word that as soon as he had sued out the divorce, if he would send me an account of it, I would come up to London and that then we would talk seriously of the matter.

It was a base design I went with, that I must confess, though I was invited thither with a design much worse, as the sequel will discover. Well, I went with my friend, as I called her, into Lancashire. All the way we went she caressed me with the utmost appearance of a sincere, undissembled affection; treated me, except my coach-hire, all the way; and her brother brought a gentleman’s coach to Warrington to receive us, and we were carried from thence to Liverpool with as much ceremony as I could desire.

We were also entertained at a merchant’s house in Liverpool three or four days very handsomely; I forbear to tell his name because of what followed. Then she told me she would carry me to an uncle’s house of hers where we should be nobly entertained; and her uncle, as she called him, sent a coach and four horses for us, and we were carried near forty miles I know not whither.

We came, however, to a gentleman’s seat, where was a numerous family, a large park, extraordinary company indeed, and where she was called cousin. I told her if she had resolved to bring me into such company as this, she should have let me have furnished myself with better clothes. The ladies took notice of that and told me very genteelly they did not value people in their own country so much by their clothes as they did in London; that their cousin had fully informed them of my quality, and that I did not want clothes to set me off; in short, they entertained me not like what I was, but like what they thought I had been, namely, a widow lady of a great fortune.

The first discovery I made here was that the family were all Roman Catholics, and the cousin too; however, nobody in the world could behave better to me, and I had all the civility shown that I could have had if I had been of their opinion. The truth is, I had not so much principle of any kind as to be nice in point of religion; and I presently learnt to speak favourably of the Romish Church; particularly, I told them I saw little but the prejudice of education in all the differences that were among Christians about religion, and if it had so happened that my father had been a Roman Catholic, I doubted not but I should have been as well pleased with their religion as my own.

This obliged them in the highest degree, and as I was besieged day and night with good company and pleasant discourse, so I had two or three old ladies that lay at me upon the subject of religion too. I was so complaisant that I made no scruple to be present at their Mass and to conform to all their gestures as they showed me the pattern, but I would not come too cheap; so that I only in the main encouraged them to expect that I would turn Roman Catholic if I was instructed in the Catholic doctrine, as they called it; and so the matter rested.

I stayed here about six weeks, and then my conductor led me back to a country village, about six miles from Liverpool, where her brother, as she called him, came to visit me in his own chariot with two footmen in a good livery; and the next thing was to make love to me. As it happened to me, one would think I could not have been cheated, and indeed I thought so myself, having a safe card at home, which I resolved not to quit unless I could mend myself very much. However, in all appearance this brother was a match worth my listening to, and the least his estate was valued at was £1000 a year, but the sister said it was worth £1500 a year, and lay most of it in Ireland.

I, that was a great fortune and passed for such, was above being asked how much my estate was; and my false friend, taking it upon a foolish hearsay, had raised it from £500 to £5000, and by the time she came into the country she called it £15,000. The Irishman, for such I understood him to be, was stark mad at this bait; in short, he courted me, made me presents, and run in debt like a madman for the expenses of his courtship. He had, to give him his due, the appearance of an extraordinary fine gentleman; he was tall, well shaped, and had an extraordinary address; talked as naturally of his park and his stables, or his horses, his gamekeepers, his woods, his tenants, and his servants as if he had been in a mansion-house and I had seen them all about me.

He never so much as asked me about my fortune or estate, but assured me that when we came to Dublin he would jointure me in £600 a year in good land, and that he would enter into a deed of settlement, or contract, here for the performance of it.

This was such language indeed as I had not been used to, and I was here beaten out of all my measures; I had a she-devil in my bosom, every hour telling me how great her brother lived. One time she would come for my orders how I would have my coach painted and how lined, and another time what clothes my page should wear; in short, my eyes were dazzled. I had now lost my power of saying no, and, to cut the story short, I consented to be married; but to be more private, we were carried farther into the country and married by a priest, which I was assured would marry us as effectually as a Church of England parson.

I cannot say but I had some reflections in this affair upon the dishonourable forsaking my faithful citizen, who loved me sincerely and who was endeavouring to quit himself of a scandalous whore by whom he had been barbarously used, and promised himself infinite happiness in his new choice, which choice was now giving up herself to another in a manner almost as scandalous as hers could be.

But the glittering show of a great estate and of fine things which the deceived creature that was now my deceiver represented every hour to my imagination hurried me away and gave me no time to think of London or of anything there, much less of the obligation I had to a person of infinitely more real merit than what was now before me.

But the thing was done; I was now in the arms of my new spouse, who appeared still the same as before, great even to magnificence; and nothing less than a thousand pounds a year could support the ordinary equipage he appeared in.

After we had been married about a month he began to talk of my going to West Chester in order to embark for Ireland. However, he did not hurry me, for we stayed near three weeks longer, and then he sent to Chester for a coach to meet us at the Black Rock, as they call it, over against Liverpool. Thither we went in a fine boat they call a pinnace, with six oars: his servants and horses and baggage going in a ferry-boat. He made his excuse to me, that he had not acquaintance at Chester, but he would go before and get some handsome apartment for me at a private house. I asked him how long we should stay at Chester. He said not at all any longer than one night or two, but he would immediately hire a coach to go to Holyhead. Then I told him he should by no means give himself the trouble to get private lodgings for one night or two, for that Chester being a great place, I made no doubt but there would be very good inns and accommodation enough; so we lodged at an inn not far from the cathedral; I forget what sign it was at.

Here my spouse, talking of my going to Ireland, asked me if I had no affairs to settle at London before we went off. I told him no, not of any great consequence but what might be done as well by letter from Dublin. “Madam,” says he very respectfully, “I suppose the greatest part of your estate, which my sister tells me is most of it in money in the Bank of England, lies secure enough; but in case it required transferring or any way altering its property, it might be necessary to go up to London and settle those things before we went over.”

I seemed to look strange at it and told him I knew not what he meant; that I had no effects in the Bank of England that I knew of, and I hoped he could not say that I had ever told him I had. No, he said, I had not told him so, but his sister had said the greatest part of my estate lay there; “and I only mentioned it, my dear,” said he, “that if there was any occasion to settle it or order anything about it, we might not be obliged to the hazard and trouble of another voyage back again”; for he added that he did not care to venture me t

oo much upon the sea.

I was surprised at this talk and began to consider what the meaning of it must be; and it presently occurred to me that my friend, who called him brother, had represented me in colours which were not my due; and I thought that I would know the bottom of it before I went out of England and before I should put myself into I knew not whose hands in a strange country.

Upon this I called his sister into my chamber the next morning, and letting her know the discourse her brother and I had been upon, I conjured her to tell me what she had said to him and upon what foot it was that she had made this marriage. She owned that she had told him that I was a great fortune and said that she was told so at London. “Told so?” says I warmly. “Did I ever tell you so?” No, she said, it was true I never did tell her so, but I had said several times that what I had was in my own disposal. “I did so,” returned I very quick, “but I never told you I had anything called a fortune; no, that I had one hundred pounds or the value of an hundred pounds in the world. And how did it consist with my being a fortune,” said I, “that I should come here into the north of England with you, only upon the account of living cheap?” At these words, which I spoke warm and high, my husband came into the room, and I desired him to come in and sit down, for I had something of moment to say before them both, which it was absolutely necessary he should hear.

He looked a little disturbed at the assurance with which I seemed to speak it and came and sat down by me, having first shut the door; upon which I began, for I was very much provoked, and turning myself to him, “I am afraid,” says I, “my dear” (for I spoke with kindness on his side), “that you have a very great abuse put upon you and an injury done you never to be repaired in your marrying me, which, however, as I have had no hand in it, I desire I may be fairly acquitted of it and that the blame may lie where it ought and nowhere else, for I wash my hands of every part of it.” “What injury can be done me, my dear,” says he, “in marrying you? I hope it is to my honour and advantage every way.” “I will soon explain it to you,” says I, “and I fear there will be no reason to think yourself well used; but I will convince you, my dear,” says I again, “that I have had no hand in it.”

He looked now scared and wild, and began, I believed, to suspect what followed; however, looking towards me and saying only, “Go on,” he sat silent, as if to hear what I had more to say; so I went on. “I asked you last night,” said I, speaking to him, “if ever I made any boast to you of my estate or ever told you I had any estate in the Bank of England or anywhere else, and you owned I had not, as is most true; and I desire you will tell me here, before your sister, if ever I gave you any reason from me to think so or that ever we had any discourse about it”; and he owned again I had not, but said I had appeared always as a woman of fortune, and he depended on it that I was so and hoped he was not deceived. “I am not inquiring whether you have been deceived,” said I; “I fear you have, and I too; but I am clearing myself from being concerned in deceiving you.

“I have been now asking your sister if ever I told her of any fortune or estate I had or gave her any particulars of it; and she owns I never did. And pray, madam,” said I, “be so just to me to charge me, if you can, if ever I pretended to you that I had an estate; and why, if I had, should I ever come down into this country with you on purpose to spare that little I had and live cheap?” She could not deny one word, but said she had been told in London that I had a very great fortune and that it lay in the Bank of England.

“And now, dear sir,” said I, turning myself to my new spouse again, “be so just to me as to tell me who has abused both you and me so much as to make you believe I was a fortune and prompt you to court me to this marriage?” He could not speak a word, but pointed to her, and after some more pause, flew out in the most furious passion that ever I saw a man in, in my life, cursing her and calling her all the whores and hard names he could think of, and that she had ruined him, declaring that she had told him I had £15,000 and that she was to have £500 of him for procuring this match for him. He then added, directing his speech to me, that she was none of his sister, but had been his whore for two years before; that she had had £100 of him in part of this bargain, and that he was utterly undone if things were as I said; and in his raving he swore he would let her heart’s blood out immediately, which frightened her and me too. She cried, said she had been told so in the house where I lodged. But this aggravated him more than before, that she should put so far upon him and run things such a length upon no other authority than a hearsay, and then, turning to me again, said very honestly he was afraid we were both undone; “for, to be plain, my dear, I have no estate,” says he; “what little I had, this devil has made me run out in putting me into this equipage.” She took the opportunity of his being earnest in talking with me and got out of the room, and I never saw her more.

I was confounded now as much as he and knew not what to say. I thought many ways that I had the worst of it; but his saying he was undone, and that he had no estate neither, put me into a mere distraction. “Why,” says I to him, “this has been a hellish juggle, for we are married here upon the foot of a double fraud: you are undone by the disappointment, it seems; and if I had had a fortune, I had been cheated too, for you say you have nothing.”

“You would indeed have been cheated, my dear,” says he, “but you would not have been undone, for fifteen thousand pounds would have maintained us both very handsomely in this country; and I had resolved to have dedicated every groat of it to you; I would not have wronged you of a shilling, and the rest I would have made up in my affection to you and tenderness of you as long as I lived.”

This was very honest indeed, and I really believe he spoke as he intended and that he was a man that was as well qualified to make me happy, as to his temper and behaviour, as any man ever was; but his having no estate and being run into debt on this ridiculous account in the country made all the prospect dismal and dreadful, and I knew not what to say or what to think.

I told him it was very unhappy that so much love and so much good nature as I discovered in him should be thus precipitated into misery; that I saw nothing before us but ruin; for as to me, it was my unhappiness that what little I had was not able to relieve us a week, and with that I pulled out a bank-bill of £20 and eleven guineas, which I told him I had saved out of my little income, and that by the account that creature had given me of the way of living in that country, I expected it would maintain me three or four years; that if it was taken from me I was left destitute, and he knew what the condition of a woman must be if she had no money in her pocket; however, I told him if he would take it, there it was.

He told me with great concern, and I thought I saw tears in his eyes, that he would not touch it; that he abhorred the thoughts of stripping me and making me miserable; that he had fifty guineas left, which was all he had in the world, and he pulled it out and threw it down on the table, bidding me take it, though he were to starve for want of it.

I returned, with the same concern for him, that I could not bear to hear him talk so; that on the contrary, if he could propose any probable method of living, I would do anything that became me, and that I would live as narrow as he could desire.

He begged of me to talk no more at that rate, for it would make him distracted; he said he was bred a gentleman though he was reduced to a low fortune, and that there was but one way left which he could think of, and that would not do unless I could answer him one question, which, however, he said he would not press me to. I told him I would answer it honestly; whether it would be to his satisfaction or no, that I could not tell.

“Why, then, my dear, tell me plainly,” says he, “will the little you have keep us together in any figure or in any station or place, or will it not?”

It was my happiness that I had not discovered myself or my circumstances at all—no, not so much as my name; and seeing there was nothing to be expected from him, however good-humoured and however honest he seemed to be but to live

on what I knew would soon be wasted, I resolved to conceal everything but the bank-bill and eleven guineas; and I would have been very glad to have lost that and have been set down where he took me up. I had indeed another bank-roll about me of £30, which was the whole of what I brought with me, as well to subsist on in the country as not knowing what might offer; because this creature, the go-between that had thus betrayed us both, had made me believe strange things of marrying to my advantage, and I was not willing to be without money, whatever might happen. This bill I concealed, and that made me the freer of the rest, in consideration of his circumstances, for I really pitied him heartily.

But to return to this question, I told him I never willingly deceived him and I never would. I was very sorry to tell him that the little I had would not subsist us; that it was not sufficient to subsist me alone in the south country and that this was the reason that made me put myself into the hands of that woman who called him brother, she having assured me that I might board very handsomely at a town called Manchester, where I had not yet been, for about £6 a year; and my whole income not being above £15 a year, I thought I might live easy upon it and wait for better things.

He shook his head and remained silent, and a very melancholy evening we had; however, we supped together and lay together that night, and when we had almost supped, he looked a little better and more cheerful and called for a bottle of wine. “Come, my dear,” says he, “though the case is bad, it is to no purpose to be dejected. Come, be as easy as you can; I will endeavour to find out some way or other to live; if you can but subsist yourself, that is better than nothing. I must try the world again; a man ought to think like a man; to be discouraged is to yield to the misfortune.” With this he filled a glass and drank to me, holding my hand all the while the wine went down, and protesting his main concern was for me.

Captain Singleton

Captain Singleton An Essay Upon Projects

An Essay Upon Projects Moll Flanders Moll Flanders Moll Flanders

Moll Flanders Moll Flanders Moll Flanders The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Everybody's Business Is Nobody's Business

Everybody's Business Is Nobody's Business Robinson Crusoe

Robinson Crusoe The Storm

The Storm The King of Pirates

The King of Pirates History of the Plague in London

History of the Plague in London Memoirs of a Cavalier

Memoirs of a Cavalier_preview.jpg) The Life and Most Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner (1801)

The Life and Most Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner (1801) A Journal of the Plague Year

A Journal of the Plague Year_preview.jpg) The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1808)

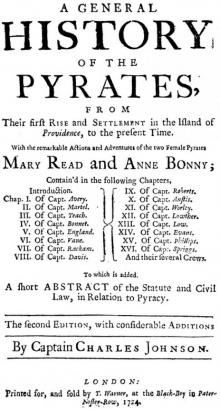

The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1808) A General History of the Pyrates: / from their first rise and settlement in the island of Providence, to the present time

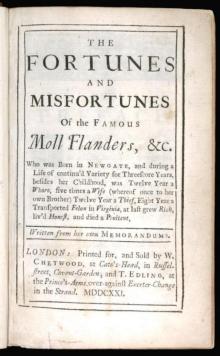

A General History of the Pyrates: / from their first rise and settlement in the island of Providence, to the present time The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders

The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders_preview.jpg) The Fortunate Mistress (Parts 1 and 2)

The Fortunate Mistress (Parts 1 and 2) Robinson Crusoe — in Words of One Syllable

Robinson Crusoe — in Words of One Syllable From London to Land's End

From London to Land's End A New Voyage Round the World by a Course Never Sailed Before

A New Voyage Round the World by a Course Never Sailed Before Roxana

Roxana The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, Volume 1

The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, Volume 1_preview.jpg) Memoirs of Major Alexander Ramkins (1718)

Memoirs of Major Alexander Ramkins (1718) Dickory Cronke

Dickory Cronke Robinson Crusoe (Penguin ed.)

Robinson Crusoe (Penguin ed.) Moll Flanders

Moll Flanders The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe rc-2

The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe rc-2