- Home

- Daniel Defoe

The Fortunate Mistress (Parts 1 and 2) Page 10

The Fortunate Mistress (Parts 1 and 2) Read online

Page 10

he was laying downthe scheme of my management, came a cart to the door with a load ofgoods, and an upholsterer's man to put them up. They were chiefly thefurniture of two rooms which he had carried away for his two years'rent, with two fine cabinets, and some pier-glasses out of the parlour,and several other valuable things.

These were all restored to their places, and he told me he gave them mefreely, as a satisfaction for the cruelty he had used me with before;and the furniture of one room being finished and set up, he told me hewould furnish one chamber for himself, and would come and be one of mylodgers, if I would give him leave.

I told him he ought not to ask me leave, who had so much right to makehimself welcome. So the house began to look in some tolerable figure,and clean; the garden also, in about a fortnight's work, began to looksomething less like a wilderness than it used to do; and he ordered meto put up a bill for letting rooms, reserving one for himself, to cometo as he saw occasion.

When all was done to his mind, as to placing the goods, he seemed verywell pleased, and we dined together again of his own providing; and theupholsterer's man gone, after dinner he took me by the hand. "Come now,madam," says he, "you must show me your house" (for he had a mind to seeeverything over again). "No, sir," said I; "but I'll go show you yourhouse, if you please;" so we went up through all the rooms, and in theroom which was appointed for himself Amy was doing something. "Well,Amy," says he, "I intend to lie with you to-morrow night." "To-night ifyou please, sir," says Amy very innocently; "your room is quite ready.""Well, Amy," says he, "I am glad you are so willing." "No," says Amy, "Imean your chamber is ready to-night," and away she run out of the room,ashamed enough; for the girl meant no harm, whatever she had said to mein private.

However, he said no more then; but when Amy was gone he walked about theroom, and looked at everything, and taking me by the hand he kissed me,and spoke a great many kind, affectionate things to me indeed; as of hismeasures for my advantage, and what he would do to raise me again in theworld; told me that my afflictions and the conduct I had shown inbearing them to such an extremity, had so engaged him to me that hevalued me infinitely above all the women in the world; that though hewas under such engagements that he could not marry me (his wife and hehad been parted for some reasons, which make too long a story tointermix with mine), yet that he would be everything else that a womancould ask in a husband; and with that he kissed me again, and took me inhis arms, but offered not the least uncivil action to me, and told me hehoped I would not deny him all the favours he should ask, because heresolved to ask nothing of me but what it was fit for a woman of virtueand modesty, for such he knew me to be, to yield.

I confess the terrible pressure of my former misery, the memory of whichlay heavy upon my mind, and the surprising kindness with which he haddelivered me, and, withal, the expectations of what he might still dofor me, were powerful things, and made me have scarce the power to denyhim anything he would ask. However, I told him thus, with an air oftenderness too, that he had done so much for me that I thought I oughtto deny him nothing; only I hoped and depended upon him that he wouldnot take the advantage of the infinite obligations I was under to him,to desire anything of me the yielding to which would lay me lower in hisesteem than I desired to be; that as I took him to be a man of honour,so I knew he could not like me better for doing anything that was belowa woman of honesty and good manners to do.

He told me that he had done all this for me, without so much as tellingme what kindness or real affection he had for me, that I might not beunder any necessity of yielding to him in anything for want of bread;and he would no more oppress my gratitude now than he would my necessitybefore, nor ask anything, supposing he would stop his favours orwithdraw his kindness, if he was denied; it was true, he said, he mighttell me more freely his mind now than before, seeing I had let him seethat I accepted his assistance, and saw that he was sincere in hisdesign of serving me; that he had gone thus far to show me that he waskind to me, but that now he would tell me that he loved me, and yetwould demonstrate that his love was both honourable, and that what heshould desire was what he might honestly ask and I might honestly grant.

I answered that, within those two limitations, I was sure I ought todeny him nothing, and I should think myself not ungrateful only, butvery unjust, if I should; so he said no more, but I observed he kissedme more, and took me in his arms in a kind of familiar way, more thanusual, and which once or twice put me in mind of my maid Amy's words;and yet, I must acknowledge, I was so overcome with his goodness to mein those many kind things he had done that I not only was easy at whathe did and made no resistance, but was inclined to do the like, whateverhe had offered to do. But he went no farther than what I have said, nordid he offer so much as to sit down on the bedside with me, but took hisleave, said he loved me tenderly, and would convince me of it by suchdemonstrations as should be to my satisfaction. I told him I had a greatdeal of reason to believe him, that he was full master of the wholehouse and of me, as far as was within the bounds we had spoken of, whichI believe he would not break, and asked him if he would not lodge therethat night.

He said he could not well stay that night, business requiring him inLondon, but added, smiling, that he would come the next day and take anight's lodging with me. I pressed him to stay that night, and told himI should be glad a friend so valuable should be under the same roof withme; and indeed I began at that time not only to be much obliged to him,but to love him too, and that in a manner that I had not been acquaintedwith myself.

Oh! let no woman slight the temptation that being generously deliveredfrom trouble is to any spirit furnished with gratitude and justprinciples. This gentleman had freely and voluntarily delivered me frommisery, from poverty, and rags; he had made me what I was, and put meinto a way to be even more than I ever was, namely, to live happy andpleased, and on his bounty I depended. What could I say to thisgentleman when he pressed me to yield to him, and argued the lawfulnessof it? But of that in its place.

I pressed him again to stay that night, and told him it was the firstcompletely happy night that I had ever had in the house in my life, andI should be very sorry to have it be without his company, who was thecause and foundation of it all; that we would be innocently merry, butthat it could never be without him; and, in short, I courted him so,that he said he could not deny me, but he would take his horse and goto London, do the business he had to do, which, it seems, was to pay aforeign bill that was due that night, and would else be protested, andthat he would come back in three hours at farthest, and sup with me; butbade me get nothing there, for since I was resolved to be merry, whichwas what he desired above all things, he would send me something fromLondon. "And we will make it a wedding supper, my dear," says he; andwith that word took me in his arms, and kissed me so vehemently that Imade no question but he intended to do everything else that Amy hadtalked of.

I started a little at the word wedding. "What do ye mean, to call it bysuch a name?" says I; adding, "We will have a supper, but t'other isimpossible, as well on your side as mine." He laughed. "Well," says he,"you shall call it what you will, but it may be the same thing, for Ishall satisfy you it is not so impossible as you make it."

"I don't understand you," said I. "Have not I a husband and you a wife?"

"Well, well," says he, "we will talk of that after supper;" so he roseup, gave me another kiss, and took his horse for London.

This kind of discourse had fired my blood, I confess, and I knew notwhat to think of it. It was plain now that he intended to lie with me,but how he would reconcile it to a legal thing, like a marriage, that Icould not imagine. We had both of us used Amy with so much intimacy, andtrusted her with everything, having such unexampled instances of herfidelity, that he made no scruple to kiss me and say all these things tome before her; nor had he cared one farthing, if I would have let himlie with me, to have had Amy there too all night. When he was gone,"Well, Amy," says I, "what will all this come to now? I am all in asweat at him." "Come to, madam?" says

Amy. "I see what it will come to;I must put you to bed to-night together." "Why, you would not be soimpudent, you jade you," says I, "would you?" "Yes, I would," says she,"with all my heart, and think you both as honest as ever you were inyour lives."

"What ails the slut to talk so?" said I. "Honest! How can it be honest?""Why, I'll tell you, madam," says Amy; "I sounded it as soon as I heardhim speak, and it is very true too; he calls you widow, and such indeedyou are; for, as my master has left you so many years, he is dead, to besure; at least he is dead to you; he is no husband. You are, and oughtto be, free to marry who you will; and his wife being gone from him, andrefusing to lie

Captain Singleton

Captain Singleton An Essay Upon Projects

An Essay Upon Projects Moll Flanders Moll Flanders Moll Flanders

Moll Flanders Moll Flanders Moll Flanders The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Everybody's Business Is Nobody's Business

Everybody's Business Is Nobody's Business Robinson Crusoe

Robinson Crusoe The Storm

The Storm The King of Pirates

The King of Pirates History of the Plague in London

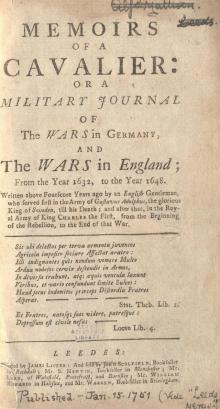

History of the Plague in London Memoirs of a Cavalier

Memoirs of a Cavalier_preview.jpg) The Life and Most Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner (1801)

The Life and Most Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner (1801) A Journal of the Plague Year

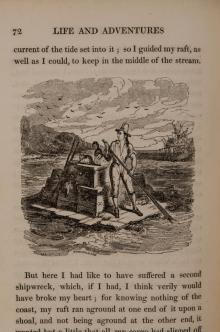

A Journal of the Plague Year_preview.jpg) The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1808)

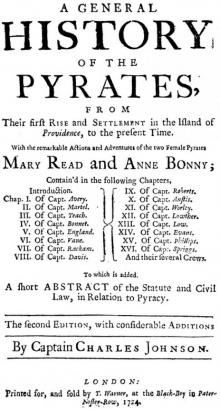

The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1808) A General History of the Pyrates: / from their first rise and settlement in the island of Providence, to the present time

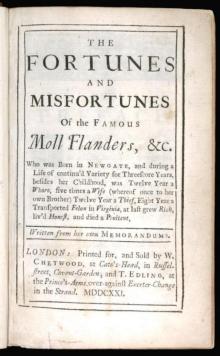

A General History of the Pyrates: / from their first rise and settlement in the island of Providence, to the present time The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders

The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders_preview.jpg) The Fortunate Mistress (Parts 1 and 2)

The Fortunate Mistress (Parts 1 and 2) Robinson Crusoe — in Words of One Syllable

Robinson Crusoe — in Words of One Syllable From London to Land's End

From London to Land's End A New Voyage Round the World by a Course Never Sailed Before

A New Voyage Round the World by a Course Never Sailed Before Roxana

Roxana The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, Volume 1

The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, Volume 1_preview.jpg) Memoirs of Major Alexander Ramkins (1718)

Memoirs of Major Alexander Ramkins (1718) Dickory Cronke

Dickory Cronke Robinson Crusoe (Penguin ed.)

Robinson Crusoe (Penguin ed.) Moll Flanders

Moll Flanders The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe rc-2

The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe rc-2